Beijing’s Influence in Europe

By Theresa Fallon, director, Centre for Russia Europe Asia Studies

China’s sway over Europe has sometimes been very visible. For instance, in 2018, European countries bathed the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Coliseum in Rome and the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin in red light in the hope of luring Chinese tourists. That same year, then-European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker unveiled a massive monument to Karl Marx, donated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), in Marx’s hometown of Trier, Germany — despite pleas from Central and Eastern European members of the European Union who had less than rosy memories of their Soviet pasts. Chinese signs are now commonplace in European airports, along with Chinese payment systems advertised on the doors to shops not only in European capitals but also in smaller towns. China’s CGTN television channel is available in hotels across Europe in a variety of local languages, alongside the China Daily newspaper, which is available for free in most venues.

Other types of influence have been less visible. Through its United Front department, the CCP has created networks of business and political elites friendly to China, a practice known as elite capture. Beijing funds European think tanks to promote good narratives about China and cozy business arrangements for people close to those in power. The allure of market access to China’s huge domestic market, along with Chinese investments in Europe, particularly in strategic infrastructure and in high-technology companies, have created dependencies.

Increasingly, China is weaponizing economic coercion. Under pressure from China, the Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson lobbied the Swedish government to reverse its ban on Chinese competitors Huawei and ZTE. China took its coercion to a new level in Lithuania for that country’s recognition of Taiwan, punishing Lithuanian companies and those outside of Lithuania that use Lithuanian components in their supply chains. China also attempts to drive a wedge between Europe and the U.S. by feeding an anti-American narrative and encouraging the EU’s “strategic autonomy,” for which Beijing has expressed its support during several meetings with EU leaders. Engaging with individual European countries, China has been particularly successful at influencing those in desperate need of Chinese funds after the financial crisis, such as Greece, and with semi-authoritarian outliers such as Hungary. In addition, Beijing has spread its influence in German business circles because Germany’s large industries depend on exports to China — following the maxim that the customer, or potentially 1.4 billion of them, can’t be wrong.

In a post-pandemic economic landscape, the need for trade, investment and other economic benefits is a more potent driver for European countries than other sources of potential influence. Nevertheless, China’s diplomatic and political influence has waned with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and dismay at Beijing’s “wolf warrior diplomacy,” which led public opinion to turn more decisively against China.

Beijing’s influence has taken different forms in different countries. An examination of individual European countries — Germany, France, Hungary, Greece and Belgium — can provide useful case studies.

Germany

China is Germany’s largest trade partner (bilateral trade was over 200 billion euros in 2020). Despite the downward trend of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe since its peak in 2016, Germany was by far the primary destination for Chinese investment in Europe in 2020 (25 billion euros). In turn, Germany’s large automotive and pharmaceutical industries (BASF, BMW, Daimler-Benz, Volkswagen), as well as industrial giant Siemens, have made direct investments in manufacturing plants in China.

In 2019, China accounted for about 40% of Volkswagen’s total automotive sales. Encouraged by Chinese authorities, German companies set up research and development centers in China. Siemens has established 20 such centers in the country, including its global headquarters for robotics. Naturally, these companies depend on the goodwill of the Chinese authorities to do business in the country. Therefore, it is not surprising that large German companies tend to toe the CCP line. For instance, in 2019 Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess stated that he was unaware of human rights abuses in Xinjiang. However, small- and medium-size companies are more sensitive to China’s unfair trade practices and appropriation of intellectual property rights. Moved by these companies, in January 2019 the German industry federation published a paper calling China not only a partner but also a systemic rival.

In December 2020, then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her EU peers insisted that the EU reach a political understanding with Beijing, resulting in the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment. One could say that Berlin has been driving EU policy on China — literally, as the German car industry is the main engine behind this. The EU is already largely open to Chinese investment, so the agreement was more about the treatment of European investors in China.

Chinese President Xi Jinping intervened personally to make last-minute concessions and conclude negotiations before the end of Germany’s rotating presidency of the EU Council, and before the administration of newly elected U.S. President Joe Biden took office. From China’s perspective, the agreement served chiefly to attract EU investment (which is useful for technological development and economic growth), to boost the international standing of China despite human rights abuses, and especially to drive a wedge into trans-Atlantic relations.

However, when the U.S. called on its European allies to send warships to the Indo-Pacific in a show of naval presence against Chinese encroachment there, Germany decided to follow the example of France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom and send a ship to the region. In August 2021, the German frigate Bayern set sail for the Indo-Pacific, crossing the South China Sea on its return trip.

In June 2021, the Bundestag passed new legislation on corporate due diligence in supply chains. The new rules, which go into effect on January 1, 2023, would oblige large German companies to check that human rights are respected before making investments abroad. This marks a signification change and signals that German companies have the legal responsibility to ascertain that human rights are respected in their supply chains. This could end German investment in Xinjiang, including the Volkswagen production facilities there. However, human rights advocates have criticized the law as not strong enough, as it only mandates due diligence of direct suppliers and covers indirect suppliers only if a company gains substantial knowledge of abuse. At the same time, during Merkel’s tenure, Education Minister Anja Karliczek launched a program to develop independent expertise on China and reduce the influence of China’s official Confucius Institutes in German education.

Merkel’s government was particularly sensitive to lobbying by large companies because large industrial groups typically support her Christian Democratic Party and are responsible for much of the country’s economic growth, tax revenue and job creation. As a result, the German government has tread very carefully with regard to China, balancing principles with economic interests to avoid upsetting Beijing.

Germany’s September 2021 general elections brought in a new government coalition composed of the Social Democrat, Green and Liberal parties. The new foreign minister, Green Party leader Annalena Baerbock, is a strong supporter of human rights and of close relations with the U.S. (though skeptical of hard power) and an outspoken China critic. However, the new chancellor, Social Democrat Olaf Scholz, was Merkel’s deputy in the previous coalition government. He follows a more cautious approach, in continuity with the previous government, seeking to balance principles and values with German economic interests. This two-pronged approach will continue to affect Germany’s China policy.

France

France is the fourth-most common destination for Chinese FDI in Europe after the U.K., Germany and Italy, with a cumulative value of completed FDI in 2000-2020 of 15 billion euros. Conversely, according to French official data, France’s FDI stock in China was worth 25 billion euros in 2017. French companies in China employ hundreds of thousands of people in manufacturing jobs. In July 2021, French prosecutors launched an investigation into the use of forced labor by French fashion goods producers in Xinjiang.

China is also a key export market for French companies. French President Emmanuel Macron is keen to promote sales of French luxury goods and of Airbus aircraft there. Also, China is a huge growth market for French farmers and other French producers.

In France, as in other European countries, surveys indicate that public opinion regarding China has deteriorated sharply in recent years. The French did not appreciate China’s handling of exports of personal protective equipment in the first stages of the pandemic or the especially aggressive style of some diplomats at the Chinese Embassy in Paris, who suggested that the French did not take good care of their aged.

Nevertheless, China’s economic power is such that Macron still seeks to maintain good relations with Beijing. In December 2020, Macron supported Merkel’s push for the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment. In July 2021, Macron, Merkel and Xi held a video summit in which Macron expressed continued support for the agreement, though he and Merkel also expressed serious concerns about the human rights situation in China.

Macron promotes a vision of strategic autonomy, whereby Europe would be less bound to the U.S. in its foreign and security policy. This is an old Gaullist idea. Macron seems to think that joining an anti-China bloc with the U.S. would be an erosion of European strategic autonomy, but seems less concerned about the effects of Chinese investment in the strategic sector of electric car batteries, an investment that brings jobs to a depressed area and that could possibly influence national elections.

In French domestic politics, Macron’s China policies have been attacked both from the right and the left. From the right, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party has accused him of outsourcing jobs to China. From the left, France Unbowed and the Socialists have accused him of not being vocal enough about human rights abuses in China.

Hungary

In 2015, Hungary was the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding with China over its One Belt, One Road program. Chinese investment in Hungary includes the construction of an upgraded, high-speed rail line between Budapest and Belgrade as part of a Belt and Road corridor between the Greek Port of Piraeus and Central Europe. Altogether, Chinese investment in Hungary remains limited in relation to the size of the economy and compared with other investors, including Japan and other Asian countries. Hungarian exports to China are also very limited.

However, China’s limited investment has paid off handsomely. Hungarian President Viktor Orbán, a nationalist and populist, has decided to align closely with China and with Russia on many international issues, snubbing the EU. Over the years, Hungary has blocked EU statements critical of China: in July 2016, on the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration against Chinese claims in the South China Sea; in May 2017, on the torture of detained Chinese lawyers; and in April 2021, when Hungary vetoed an EU statement criticizing China over Hong Kong. In June 2021, Hungary, along with Cyprus, Greece and Malta, opposed an EU statement at the United Nations Human Rights Council over human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

There is growing opposition to this pro-China policy in Hungary, as more people see that it has benefited only a small, well-connected elite. Orbán’s plans to open a new campus of China’s Fudan University in Budapest sparked street protests. That city’s left-leaning mayor decided to name streets after the Dalai Lama and others likely to incense China.

Greece

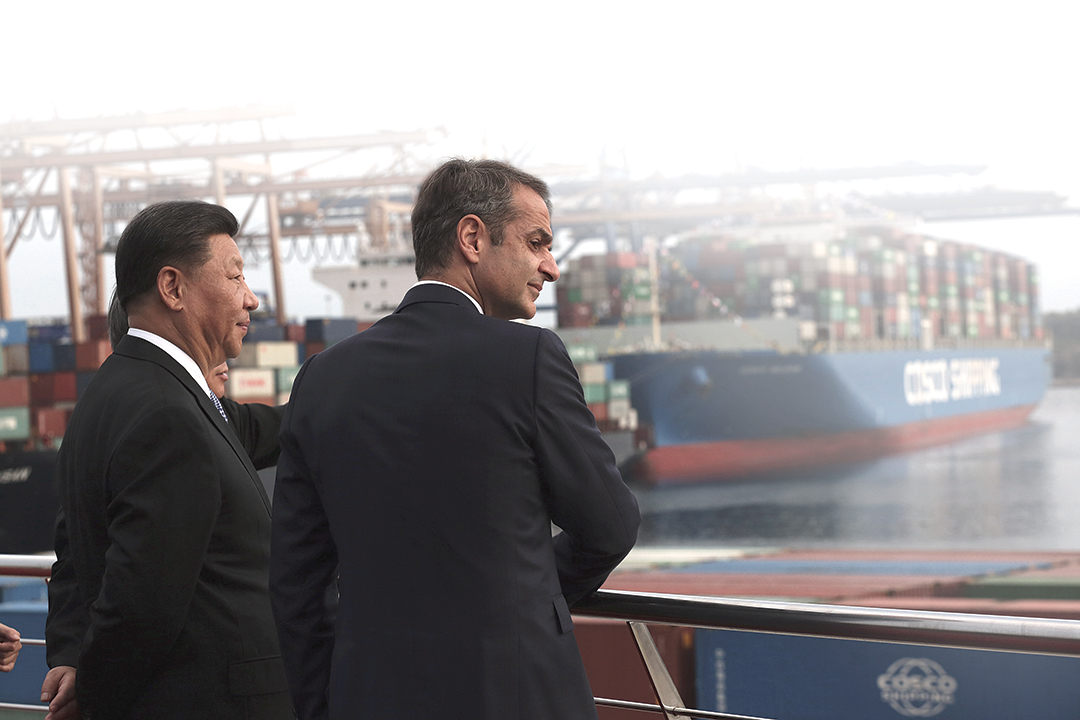

Chinese FDI in Greece increased dramatically after the 2008 world financial crisis and the 2009 Greek government debt crisis. China found that Greek assets were cheap, and Greece desperately needed the money. In particular, China invested in the main Greek Port of Piraeus. During a visit by then-Chinese President Hu Jintao in November 2008, China’s state-owned China Ocean Shipping Company Pacific (COSCO) signed a $1 billion deal for a 35-year concession to operate and manage two container terminals at the port. In 2016, COSCO acquired a controlling stake of the port.

With hindsight, one may wonder whether it was wise for richer European nations and for the U.S. to let Greece fend for itself during the financial and debt crisis, allowing it to sell off strategic assets to a cash-rich outside power at fire-sale prices, rather than injecting the necessary cash to allow the country to withstand the crisis. The Port of Piraeus soon became one of the key nodes in the Belt and Road program, connecting China with Europe by land and by sea. It allowed China to establish a foothold in Southern Europe, with plans to upgrade the rail line from Piraeus to Budapest.

Chinese investment in Greece has clearly translated into diplomatic and political influence, as the Greek government strives to preserve its good relations with Beijing. For example, in July 2016 Greece sided with Hungary and Croatia to prevent strong EU language supporting the ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague against Chinese claims in the South China Sea. In June 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement critical of China at the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva. Greece called the statement “unconstructive criticism of China.” In September 2017, when the European Commission proposed a mechanism for screening FDI in the EU, Greece initially opposed it. France and Germany were particularly keen on this mechanism, which would examine foreign investment in strategic assets, such as the Chinese investment in the Port of Piraeus. Eventually, in 2019, Greece agreed to a weaker FDI screening mechanism, whereby the commission issues nonbinding opinions but each EU member state makes the decisions on foreign acquisitions within its own borders.

China’s influence on Greece did encounter some limits when it collided with core Greek interests on cultural heritage and social fabric. In 2019, Greece suspended construction of new facilities at the Port of Piraeus when it emerged that it would destroy archeological sites. Greece has also acted to counter COSCO efforts to weaken port workers’ trade unions.

Greece is a member of China’s 16+1 format to expand cooperation with Central and Eastern European countries. Internationally, Greece often sides with China on issues of territorial integrity because of Greece’s support for the reunification of the divided island of Cyprus. However, China’s influence on Greek foreign policy is tempered by Greece’s pursuit of its own national core interests and its desire to preserve good relations with the U.S. and with European partners. Notably, Greece needs support from the U.S. and Europe, including France, in its standoff against Turkey in the eastern Mediterranean. As a country with a worldwide shipping industry, Greece, in April 2021, supported the new EU strategy on the Indo-Pacific, which includes protecting the sea lines of communication and upholding the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, under which China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea were refuted by the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Belgium

The Chinese presence in Belgium’s economy includes the China Belgium Technology Center at the University of Louvain-la-Neuve, and a large logistics park at the Port of Zeebrugge, where construction started in June 2021. China is also the No. 1 client of the Belgian Microelectronics Research Centre.

Belgium has a special place as the country that hosts EU institutions in its capital, Brussels. China has provided funding to Brussels-based think tanks to promote Chinese narratives. For instance, the Friends of Europe think tank has been hosting annual Belt and Road conferences and has been sending young European leaders to visit China.

Ahead of Xi’s visit to Brussels in March 2014, China donated a 10,000-volume library on China studies and computers to the College of Europe in the historic town of Bruges. In addition to Confucius Institutes and a special cultural center near the EU institutions in Brussels, China has been offering special exchange visits to a school in Shanghai for students at the European schools that teach the children of EU officials. The University of Ghent has also been sending students to China every year on an exchange program largely funded by the CCP.

China’s lobbying efforts in Brussels include the opening in 2019 of a Huawei Cyber Security Transparency Centre, to convince European officials and companies of the transparency and reliability of Huawei 5G standards. European speakers at the opening ceremony included a member of the European Parliament and a former president of the German Federal Network Agency.

Chinese influence activities in Brussels have not been limited to soft power and lobbying. A Chinese academic with links to Belgian universities has been barred from Belgium because of his involvement in espionage. Former EU officials and think tank employees have been accused of improperly passing information to China. Computers donated to the College of Europe were found to be full of spyware. Spying devices were also found in the building that Chinese contractors built for the Maltese mission to the EU, just opposite EU headquarters.

After the spread of COVID, Chinese influence activities in Brussels, including visits and exchanges, have naturally abated, while China’s response to the pandemic and increased crackdowns in Xinjiang and Tibet — which sparked EU sanctions and Chinese countersanctions in March 2021 — have alienated public opinion and strengthened the voice of China critics, especially in the European Parliament.

Conclusion

Through economic, political and diplomatic tools, and through elite capture, China has been increasing its influence in Europe. Large companies have willingly turned a blind eye to human rights abuses because of their business interests. Governments have been wary of irritating China in international forums. Hungary is a particularly troubling case because it has moved toward authoritarianism and has been seeking support from China to balance the EU’s demands for rule of law and liberal democracy.

However, the pandemic seems to have been a watershed moment. Public opinion in Europe has become wary of China’s initial withholding of information, of its weaponization of Chinese-made personal protective equipment (which showed the need to diversify supply lines), and its even harsher crackdown on human rights, especially in Xinjiang and in Hong Kong. Public opinion surveys show a deterioration of the public’s perception of China across the board. Powerful economic interests still influence the policies of European countries toward China, but the balance of public opinion and public policy seems to have tilted to a critical view of the country. Hungary’s support for the global minimum corporate tax rate in October 2021 also shows that Hungarian policy is more closely tied to EU economic policy despite other policy differences, and that China’s influence over Orban’s government has limits.

Comments are closed.