The pandemic’s impact on the Middle East and North Africa

By Mariusz Rzeszutko

Before the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic, countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) were at a crossroads. Ten years after the Arab Spring, and as a result of unsuccessful reforms, MENA societies had returned to a state of growing dissatisfaction with the decade’s changes. Following protests in Iraq and Lebanon, social turmoil spilled out in Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia and Iran, while the situations in Libya and Sudan became significantly more complex.

The region’s circumstances changed considerably with the emergence of COVID-19. It not only revolutionized the sociopolitical and economic situation, but also seriously challenged governments and their crisis management abilities. Although each government chose its own management style and policies, most COVID-19 measures were quickly weaponized in fights with political opponents. Moreover, the spread of the virus also provided a wide range of tools to introduce restraints and public control.

Due to the size of the MENA region and editorial limitations, only certain countries will be analyzed here. They were selected for political and economic stability and the political systems and changes taking place therein: from Lebanon, which is transforming toward a technocratic government, through authoritarian Algeria, to the absolute monarchy of Saudi Arabia.

Pre-COVID-19

Although Lebanon’s internal policies maintained political stability, avoiding conflicts between religious groups, the government failed to implement long-promised political and social reforms, which contributed significantly to the deterioration of the economic situation. A protracted crisis associated with the inability to agree on the heads of cabinet and accelerated by the poor economic situation led to escalating dissatisfaction in October 2019, and consequently to protests.

In Algeria, an authoritarian country with a hybrid system of central control and capitalism, protests are ongoing against authorities associated with ex-President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s regime and the disputed presidential election of December 2019.

Apart from the worldwide condemnation over the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi, which caused a significant outflow of foreign capital and shook the economy, Saudi Arabia has not struggled with social protests or economic collapse. Thus, it had a much easier start in the fight against the pandemic.

Identification and measures taken

In Lebanon, the first COVID-19 cases were officially recorded in February 2020 and were assumed to have arrived with airline passengers. The main outbreak of infection was in Beirut, from where it spread in large clusters. Authorities had only a few hundred test kits and space to isolate only 200 patients. The first fatalities had already occurred by the end of February. Lebanon began preventive campaigns, encouraging compliance with hygiene protocols and declaring restrictions on people coming from countries where the virus was confirmed. Within two weeks of the official announcement of the first infections, the government quickly decided on countermeasures, including steps with economic consequences.

Authorities declared a state of emergency, shutting down cultural and educational centers and border crossings. Restrictions were introduced: a curfew, a ban on gathering and organizing mass events, and orders to work in shifts in government ministries and other places necessary for the functioning of the state. The availability of commercial and banking facilities was significantly reduced, but pharmacies and petrol stations remained open. Many private health care facilities were transformed into isolation wards, and seaside resorts were used as places of self-isolation. There were appeals to the public, especially those over 65 years old, to stay at home. In March 2020 the government, trying to adapt to the dynamic situation, introduced restrictions similar to those enforced in European countries and considered a matter of state security. However, the decision-making process was noticeably chaotic.

The main burden of fighting the pandemic — from distributing aid and securing the transport of people and medical supplies, to patrolling cities — fell to the Lebanese military and (informally) Hezbollah in the area it controls independently of the government. Due to the dramatic economic situation, in April 2020 authorities introduced a five-phase plan to gradually reopen the country. In September, after another wave of COVID-19 cases, the Crisis Management Project was modified to classify geographical sectors into risk zones based on the United States Department of Health and Human Services system: The first/white zone meant very low risk of infection, while the fourth/red zone was characterized by a high risk of infection.

Restrictions were imposed on each zone depending on risk classification: from requirements to wear masks and maintain social distancing, to close monitoring of social contacts, to restricting movement in red zones. To better manage the zones, the Lebanese government created a digital platform to support the enforcement of social discipline. When the situation failed to improve under the partial restrictions, the government implemented a total lockdown in November 2020. Restrictions were loosened before Christmas, but due to the resulting increase in infections, a full lockdown was re-introduced in January. In February, the government announced a limited easing of the restrictions on movement and public services.

Algeria implemented a slightly different scenario. While most of its measures were in line with those adopted by Lebanon, the Algerian authorities reacted quickly to the spread of the virus. Direct airline connections between Algiers and Beijing were suspended at the beginning of February 2020. At sea, land and air border-crossing points, extraordinary control measures and thermal imaging cameras were introduced. The country launched a media information campaign. As happened in Lebanon, social media reported unofficially about the first deaths in February 2020. Similar to Lebanon, the Algiers authorities denied these reports. However, at the end of February, under pressure because of published reports about the virus, Health Minister Abderrahmane Benbouzid confirmed the first cases of COVID-19, which most likely reached Algeria from Italy. More infections, thought to be from France, were also announced.

In the face of the accelerating spread of the virus in March 2020, the Ministry of Health decided to forcibly postpone the holidays of all doctors and medical personnel. Instructions were issued to ministries, offices and workplaces to take preventive and protective measures at places of work. Elderly and chronically ill people were ordered to avoid unnecessary contact. For preventive purposes, pharmacies were instructed to save their stocks of protective masks for medical personnel only. In early March, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune decided to close educational centers, and air and sea connections were suspended. Sports, cultural and political gatherings were banned. It was also decided to ban the export of strategic products, both medical and food, until the crisis has ended. The president authorized the National People’s Army and the police to fight the virus by controlling the flow of people using increased checkpoints on roads into major cities, restricting access to vilayets, conducting assisted and even forced transport of people to places of isolation, and transport and distribution of materials (masks, decontamination gels etc.). Authorities quickly decided to issue 1.5 million masks to citizens and to order another 54 million as a reserve.

The minister of religion suspended public prayer gatherings — an action unheard of in Arab countries — ordering the closure of mosques and all places of worship. Court hearings in criminal cases were suspended. A special instruction from Prime Minister Abdelaziz Djerad imposed a number of restrictions and penalties on citizens who failed to comply with the government’s directives. For instance, refusal to self-isolate was punishable by imprisonment for two to six months and a significant fine. The Scientific Commission for Monitoring and Assessment of the COVID-19 Pandemic was established to monitor and manage the crisis: Crisis cells were launched at the level of state institutions, and crisis management units were established in wilayat (administrative districts).

With technical support from the World Health Organization (WHO), the National Institute of Public Health initiated a process of support and capacity building to coordinate responses to the epidemic. The government also introduced a system of assistance and support for citizens to mitigate the negative economic and social impacts of the protective measures. It established a scientific committee to study COVID-19, created a campaign to clean and disinfect public spaces regularly, and authorized the army to fight market speculation in goods for basic needs. Despite rising infection numbers in Algeria, Djerad expanded the list of permitted commercial activity deemed necessary to avoid economic collapse, and the Directorate-General for Taxation announced new measures to alleviate the effects of the crisis on businesses. The government, under an accelerated procedure, facilitated the import of goods to counter the epidemic (primarily pharmaceutical products, medical equipment and basic food items). Some senior officials and military leaders, to help mitigate the financial effects of the crisis, agreed to transfer their monthly salaries to a solidarity fund.

Saudi Arabia quickly introduced a number of restrictions similar to those of European countries to reduce transmission of the virus and, among the countries analyzed, showed the greatest effectiveness in combating COVID-19.

Already by March 2020, flights and permits for citizens to travel to neighboring countries, as well as to Italy and Korea, were suspended. Sea transport options were limited. Similar to Algeria, commercial facilities were closed and access to services was severely restricted. However, pharmacies and supply companies remained open. Early on, the Saudi Food and Drug Authority began testing the effectiveness of disinfectants in eliminating the virus, and substandard disinfection measures were published on the agency’s website. Grocery stores were allowed to remain open with a condition that items exposed to frequent contact by customers be frequently sterilized. Catering services were allowed to stay open as take-out only. Apps for the delivery of food and medicine were quickly introduced. Electronic transactions were welcomed to prevent transmission of the virus through banknotes. Supporting e-platforms were effectively developed and adapted to meet the needs of citizens. Mobile virus testing points were established.

Authorities mandated that people in vulnerable groups be allowed to work remotely, and employers had to strictly respect these provisions. The government ordered the implementation of a special tab on the Mawid (e-health services) platform, enabling registration with a doctor and being able to receive an early diagnosis using a mobile application. Punishment was imposed on medical and paramedical personnel who intentionally concealed or delayed providing information about a COVID-19 infection.

To fight the pandemic, medical care was extended to people staying illegally in Saudi Arabia or those who did not submit documents. Curfew violations were punishable by a heavy fine, and recidivism could lead to imprisonment.

Scheduled military activities, including internal exercises and exercises with foreign partners, were canceled. Control over the business services sector was also maintained, preventing speculation on the prices of basic necessities and health care products. Similar to Algeria, religious gatherings were suspended. The state immediately implemented control over resources by verifying the number of necessary goods and food products. In mid-March, the Saudis, like the Algerians, stopped the export of medicines and medical devices. A campaign providing citizens with free protective measures against virus transmission was launched.

Scheduled military activities, including internal exercises and exercises with foreign partners, were canceled. Control over the business services sector was also maintained, preventing speculation on the prices of basic necessities and health care products. Similar to Algeria, religious gatherings were suspended. The state immediately implemented control over resources by verifying the number of necessary goods and food products. In mid-March, the Saudis, like the Algerians, stopped the export of medicines and medical devices. A campaign providing citizens with free protective measures against virus transmission was launched.

King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, in clear and concise messages, informed the nation about the government’s activities and the state of emergency, preparing the public for a potentially deteriorating scenario. To limit the economic consequences of the pandemic, the government prepared stimulus packages for the private and banking sectors at the end of March 2020. The state-owned energy company provided services despite the lack of payments from citizens. Attempts to speculate, monopolize or inflate prices were severely punished.

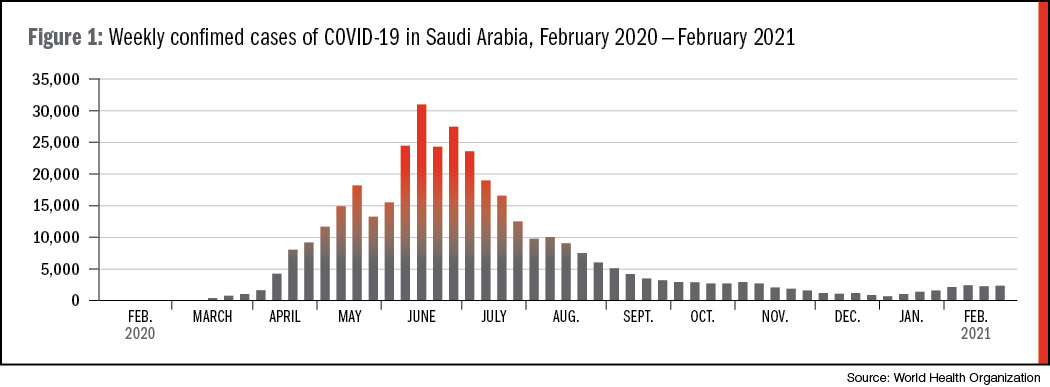

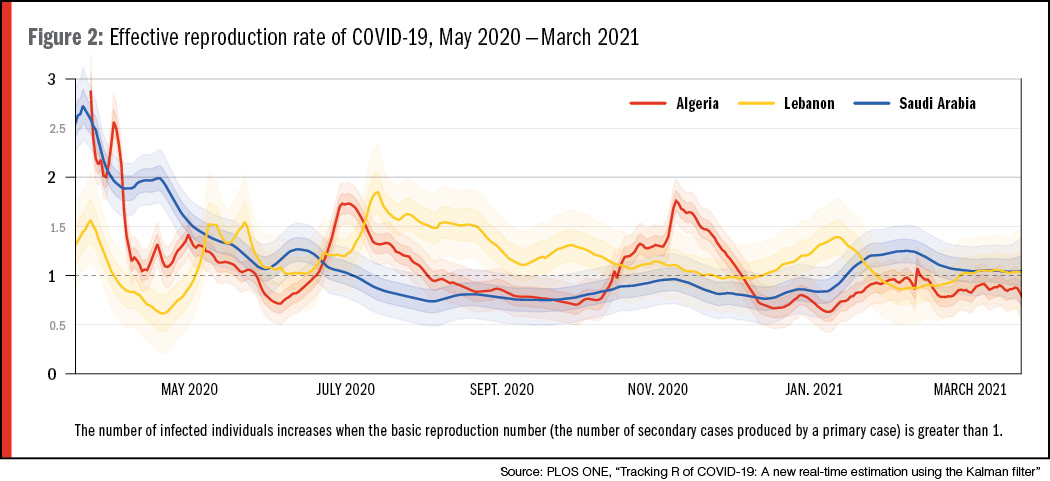

Self-isolating people were placed in hotels, thanks to government subsidies. Industry, agriculture, energy and the health sectors also received subsidies. Funds earmarked for large projects were redirected to maintain the state’s economy. As a result of these measures, the virus’s effective reproduction rate (R index) and the number of reported cases began to decline significantly, which allowed the government to announce a three-stage plan for removing the restrictions. In addition, the Saudis decided to financially support Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, a global health partnership created to promote vaccine development and immunizations.

Deficiencies and societal judgments

In Lebanon, the public accused the Ministry of Health of disregarding the seriousness of the threat, being unprepared for a global pandemic and sluggishly responding to the crisis. Passengers arriving at the airport were randomly selected for rudimentary screening, such as temperature checks. Workers were not properly equipped with protective gear, exposing them to the virus and potentially spreading it to healthy travelers.

Authorities were also criticized for failing to effectively enforce restrictions. Under public pressure, the government suspended travel connections first with Italy and Iran and later with other countries. As the situation deteriorated, the Lebanese government reduced traffic by allowing the use of vehicles with odd registration numbers on some days and those with even numbers on the others. However, the number of exceptions (including diplomats, the Army, security services, doctors, journalists, food suppliers and garbage collectors) significantly limited the intended risk reduction.

In addition, the public’s compliance with the restrictions loosened over time. Gross violations of social distancing regulations were regularly presented in the media. Increasingly expensive fines had little effect, even in the face of the predicted May infection peak. In this context, there was a clear contrast between government-controlled areas and those overseen by Hezbollah. Restrictive measures taken by Hezbollah and Amal, such as motorized patrols and independent checkpoints, enforced preventive measures within the local populations.

Lebanon was saved by the fact that in the first wave of infection, more than 67% of those infected suffered relatively mild symptoms and only 9% of patients were in critical condition. The second wave of the virus, which emerged at the beginning of September, changed the situation significantly. Although the virus reproduction rate was much lower, the number of daily infections exceeded the capacity of the health care service, with almost 100% usage of ventilators and an increased number of deaths in younger patients. It led the government to cooperate with Hezbollah, an unofficial competitor that financed preventive measures and operated some medical reserve centers to take pressure off state health services. Some critics also condemned what they considered a reckless use of military resources reserved for war.

Lebanon was saved by the fact that in the first wave of infection, more than 67% of those infected suffered relatively mild symptoms and only 9% of patients were in critical condition. The second wave of the virus, which emerged at the beginning of September, changed the situation significantly. Although the virus reproduction rate was much lower, the number of daily infections exceeded the capacity of the health care service, with almost 100% usage of ventilators and an increased number of deaths in younger patients. It led the government to cooperate with Hezbollah, an unofficial competitor that financed preventive measures and operated some medical reserve centers to take pressure off state health services. Some critics also condemned what they considered a reckless use of military resources reserved for war.

The drastic increase in infections in May 2020 was likely the result of the resumption of social protests caused by the pauperization of society and income losses due to restrictions imposed by the state. The situation was reinforced by the illusory feeling of security because of falling transmission indicators early on.

In Algeria, independent observers were alarmed when the government’s assurances of increased controls at airports and ports were not realized. The credibility of governmental information on resources and strategies also raised doubts among citizens and journalists. One of Algeria’s most questionable decisions was to repatriate more than 130 Algerians who had been residing in China, 31 of them from the epicenter of the virus — Hubei province. Given the poor security measures and lack of preparation in a country mired in internal protests, the idea of bringing in so many potentially infected people was poorly received by the public. Additionally, April’s repatriation of Algerian citizens from Turkey incurred a high risk of bringing terrorists associated with the Islamic State into the country.

At the end of February 2020, the WHO alerted the world about the inability of African countries to deal with the pandemic. Following this announcement, Algerian authorities began censoring state media, effectively eliminating the possibility of leaking negative information, as had happened with the Algerian cholera outbreak in 2018. Therefore, independent media argued that the number of COVID-19 infections in Algeria may be much greater than what was announced by authorities. The public began to buy masks and disinfectant gels. People began to stockpile food and water. In just two weeks, cases of the virus were recorded in various wilayat. A particular failure of Algeria was its total lack of control over Chinese citizens living and working there, an estimated 400,000 to 1 million. These people, working in rotation, were not tracked by authorities within Algeria, nor were their movements tracked when moving between China and Algeria. The multivector actions taken to reduce the risk of spreading the virus were not sufficient, nor was the efficiency of the Algerian health service.

In Saudi Arabia, due to limitations on freedom of speech, only slightly negative signals reached the press. In typical Saudi manner, authorities forced citizens to respect the ban on creating and publishing photos and recordings of curfew violations. Breaking the order could result in punishment of up to five years imprisonment and exorbitant fines. Despite numerous preparations and innovative solutions in places, Saudi Arabia did not protect itself against the negative economic effects of the pandemic. To stabilize budget revenues, authorities increased value-added taxes and customs duties on imported food.

COVID-19 as a political tool

MENA authorities soon realized not only the health, economic and societal risks of the global virus, but also the political benefits it could bring. At the beginning of March 2020 in Lebanon, where there had been ongoing protests demanding a technocratic government, authorities banned mass events. Schools and colleges, which had played a significant role in organizing the protests — led mainly by the younger generations — were closed as well. To keep public order, mixed patrols of the army and internal security services were implemented and entitled to check the identification of citizens and use coercive measures or detention. Limiting the possibility of protests allowed the government to work to save the country from collapse and implement reforms required by the international community, a condition for receiving international aid. Despite the atmosphere of the persistent epidemic threat, intensifying social protests in more urbanized regions resumed in July. In the opinion of authorities, the protests created a situation that risked spreading the virus. Lebanese authorities have used COVID-19 to distract from the deepening political and economic crisis in the country and the failure of the main political blocs to build consensus and form a new government.

The COVID-19 pandemic, one of Algeria’s biggest challenges, paradoxically constituted salvation for the authorities and, in retrospect, significantly helped the government to restore the country’s internal stability. Stigmatized by protesters for failing to fulfill election promises, the new government gained tools to suppress the Hirak social street movement, which since February 2019 has been demanding the resignation of politicians associated with the former president’s regime. A ban on gatherings and the requirement to quarantine solved a theoretically unsolvable problem at no cost, both in terms of image and the economy. Algerian authorities assigned blame for the developing pandemic on the relentless Hirak, which they believe greatly contributed to the spread of the virus. They also called for an end to excessive use of public spaces, alleging support for the movement from third countries. Soon authorities adopted a repressive attitude toward the protesters. On the viaducts over the highways to Algiers, the number of national gendarmerie observation posts increased to respond to crowds heading to join Hirak protests. The virus’s spread was quickly used by President Tebboune to temporarily restrict civil liberties. Contrary to previous assurances of respect for Hirak, Tebboune strictly banned organizing and participating in rallies and marches, totally freezing Hirak activity.

Lessons learned

Lebanon’s efforts to fight COVID-19 are undeniable, although the consequences of concealing the real state of the disease in the first few weeks hindered any attempt to slow the infection’s spread. The second wave that started in September exceeded the worst expectations, mainly due to the high percentage of people requiring hospitalization in intensive care units. A new crisis management plan, broken down into security zones, mainly aimed at fighting the virus ad hoc without presenting any reasoned strategy. Imposing obligations on the Army that are completely unrelated to its statutory tasks has disrupted the balance between protecting the nation’s security and fighting terrorism. This situation could easily be exploited by neighboring countries, terrorist groups or religious militias, or lead to a potential junta. The state’s biggest problem, however, was its inability to control a society that did not comply with restrictions. As Health Minister Hamad Hasan admitted in November 2020, partial blockades did not bring the expected results.

Lebanese authorities did not use the experiences gained during the first wave, instead repeating the reactive fight against the virus’s spread. This contributed to a significant deterioration of the situation during the second wave of infections in the fall, at a time conducive to much faster transmission. In light of the decisions made by authorities, the effectiveness of the implemented programs largely depended on the discipline of citizens, which left much to be desired. On the other hand, imposing draconian restrictions on all sectors of the economy resulted in a significant decrease in quality of life, the loss of jobs and even livelihoods by many Lebanese who, frustrated, began to worry more about taking care of their families than being infected.

In Algeria, a lack of information about COVID-19 caused Algerians to disregard the fast-growing threat. Authorities allowed life on the streets to continue as it did before the pandemic, despite the announced restrictions. State media adopted a strategy of blaming foreigners and tourists for spreading the virus in Algeria. The president granted powers to prosecute those who spread disinformation and panic, such as calls to buy and hoard large amounts of food. On one hand, this action provided an effective tool for fighting disinformation; on the other, it was also useful in the authoritarian fight against societal opposition. Contrary to chaotic Lebanon, the Algerian government conducted a decisive and well-coordinated mobilization of crisis management units, which may become an example for other countries. Most likely, this was due to a centralized system of power concentrated in a narrow group of decision-makers.

Another example worth appreciating is the government’s control of the market to eliminate the shortage of necessary foods, which helped reduce panic among the citizens. Despite the growing number of COVID-19 cases in Algeria, Prime Minister Djerad, after consulting with ministerial units, expanded the list of permitted forms of commercial activity deemed necessary for society, thus preventing an economic collapse, and the Directorate-General for Taxes announced new measures to mitigate the effects of the crisis on enterprises. The government, under an accelerated procedure, facilitated the import of goods to counter the epidemic. Another lesson was the government’s loss of vigilance in the cyber realm while dealing with the pandemic, which allowed hackers to access sensitive information about state-owned companies.

Among these countries, Saudi Arabia coped the best with the successive waves of COVID-19, learning from the mistakes of Euro-Asian countries and drawing appropriate conclusions. Unlike Lebanon or Algeria, Saudi authorities did not hide the presence of the virus and immediately began implementing measures to reduce its transmission. Restrictions on suspect visitors from other countries reduced the number of cases from the very beginning. Saudi Arabia took steps to lessen the risk of virus transmission from Yemen and supported its southern neighbor, which would not have been able to cope without outside assistance.

As a lesson learned, Saudi Arabia should examine a policy in Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s Vision 2030 plan that includes a policy for reducing the number of foreigners in the domestic labor market. As this crisis highlighted, about 80% of doctors and nurses in the kingdom are foreigners who turned out to be irreplaceable during the pandemic. The Saudi success was helped by the provision of medical care for its citizens and the effective implementation of a virus-testing project. Contrary to the authorities in some European countries, the Saudis approached the downward trend of cases with a great deal of rationalism, while obtaining information from around the country and maintaining full control of the situation. Authorities also efficiently denied fake news, allowing Saudi Arabia to maintain peace and discipline.

Comments are closed.