The likely scenarios and their consequences

By Dr. Drew Ninnis, Marshall Center alumni scholar

“How much anger those European gentlemen have accumulated!” proclaims Andrei Danilovich Komiaga, a loyal oprichnik (guardsman) of the new czar. “For decades they have sucked our gas without thinking of the hardship it brought our hardworking people. What astonishing news they report! Oh dear, it’s cold in Nice again! Gentlemen, you’ll have to get used to eating cold foie gras at least a couple of times a week. Bon appétit! China turned out to be smarter than you …”

At least, that is the Russian (and Chinese) future that the post-Soviet provocateur Vladimir Sorokin depicts in his novel, Day of the Oprichnik. Set in the New Russia of 2028, the czarist regime is back in full swing and has erected a big, beautiful wall on its border with Europe to keep out the “stench [of] unbelievers, from the damned, cyberpunks … Marxists, fascists, pluralists, and atheists!” Russia is rich and awash in Chinese technology but inward looking, while reverting to the feudal structures of Ivan the Terrible (or the Formidable as this new generation of Russian leaders might have it).

While the answer that Sorokin provides may be fanciful, the questions he poses are worth asking — what might Russia look like in 2028 and beyond? Does Russia’s future include China? And what are the consequences of these potential futures for Europe and the rest of the world? The intertwined trajectories of Russia and China will force consequential decisions for the United States, Europe and their allies that will shape the 21st century. One way to anticipate, inform and prepare for these decisions is by contemplating the potential futures they might imply.

Of course, the future is inherently uncertain and futures analyses, such as this one, deal less in making likely calls about the future and more in envisioning future scenarios. This isn’t done entirely in the flamboyantly satirical style of Sorokin; instead, the analysis below considers key trends and indicators, available empirical data for tentative forecasts, and counterfactual cases before offering a range of possible future scenarios.

This analysis divides the questions of Russia’s and China’s potential futures into several sections: first, considering their mutual history and the possible ways in which these may be used; second, by considering the potential trends and futures of both; third, by examining the central role that China’s One Belt, One Road program has in shaping those futures; and finally, by considering the potential scenarios and strategies within these futures.

These speculations have a fundamental policy application, prompting clear thinking on which of these futures might we prefer and what can be done to achieve the best possible future for all. Ultimately, it is far better to have planned for many potential responses and not need them than to be caught by surprise and without options.

Potential futures for China

Let us turn to China’s future, and in particular the trends and sectors that are likely to define the realm of the possible. These are: China’s physical environment, its demographics, its economy, Chinese politics and society, and China’s foreign relations and security. Finally, what are China’s future strategies likely to be and what options does China have in pursuing them.

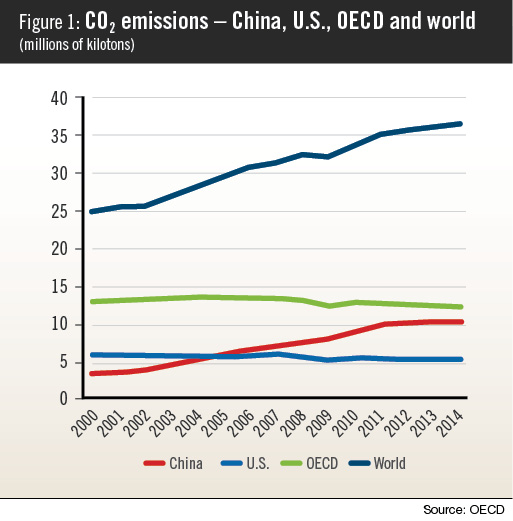

In short, China’s environmental future does not look good — and that’s bad news because environmental trends are the least likely to suddenly turn around, and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) options in tackling these long-term trends are limited. As Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data indicate, China’s CO2 emissions are approaching those of the developed world combined and, without drastic intervention, are likely to dramatically exceed them by 2050 (Figure 1). While it has made some progress in increasing nonrenewable electricity production, China lags behind most other developed nations.

While this has significant global consequences, it also has severe local consequences. China’s arable land has decreased dramatically, from 118 million hectares in 2000 to 106 million just 15 years later, while its population has continued to grow — making food security a huge issue. Compare this to the U.S., which over the same period went from 175 million hectares down to 154 million. While this is also a sharp decrease, it indicates that despite the short-term effects of the ongoing trade war with the U.S., China is likely to remain dependent on agricultural imports from the U.S. unless it can quickly grow the number of trade-partner farming superstates through One Belt, One Road.

While this has significant global consequences, it also has severe local consequences. China’s arable land has decreased dramatically, from 118 million hectares in 2000 to 106 million just 15 years later, while its population has continued to grow — making food security a huge issue. Compare this to the U.S., which over the same period went from 175 million hectares down to 154 million. While this is also a sharp decrease, it indicates that despite the short-term effects of the ongoing trade war with the U.S., China is likely to remain dependent on agricultural imports from the U.S. unless it can quickly grow the number of trade-partner farming superstates through One Belt, One Road.

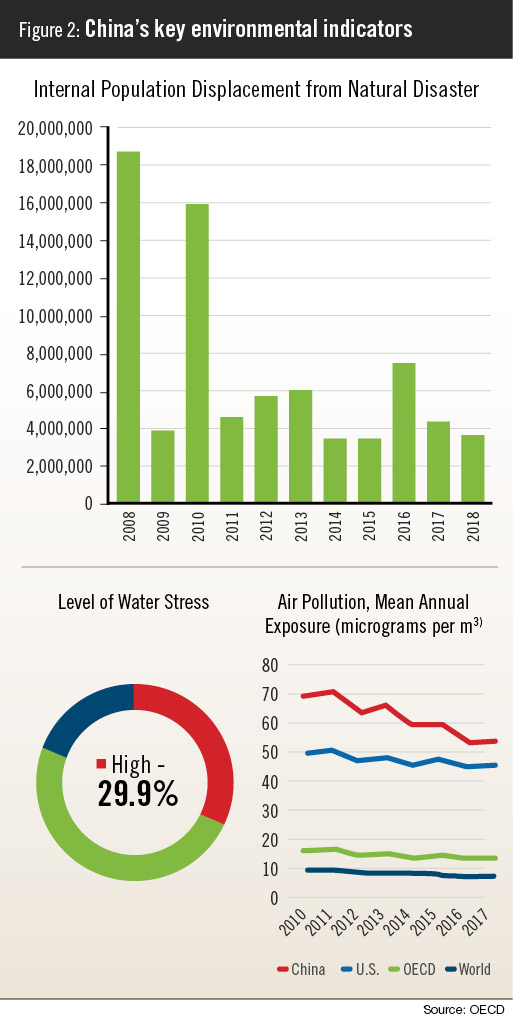

Other environmental indicators for China tell a similarly alarming story — with the number of people internally displaced by natural disasters remaining high, averaging 7 million each year. Its level of water stress is extremely high, and the mean annual exposure to air pollution far outpaces the rest of the world (Figure 2).

The point of this survey is to establish that China faces significant limits on the growth of its other sectors (demographics, economy) that stem directly from the future environmental problems it will face. A key source of these problems is the water-food-energy nexus, because as these environmental issues grow alongside Chinese demand for food and energy, there will be less and less water or other key inputs to support this growth.

The point of this survey is to establish that China faces significant limits on the growth of its other sectors (demographics, economy) that stem directly from the future environmental problems it will face. A key source of these problems is the water-food-energy nexus, because as these environmental issues grow alongside Chinese demand for food and energy, there will be less and less water or other key inputs to support this growth.

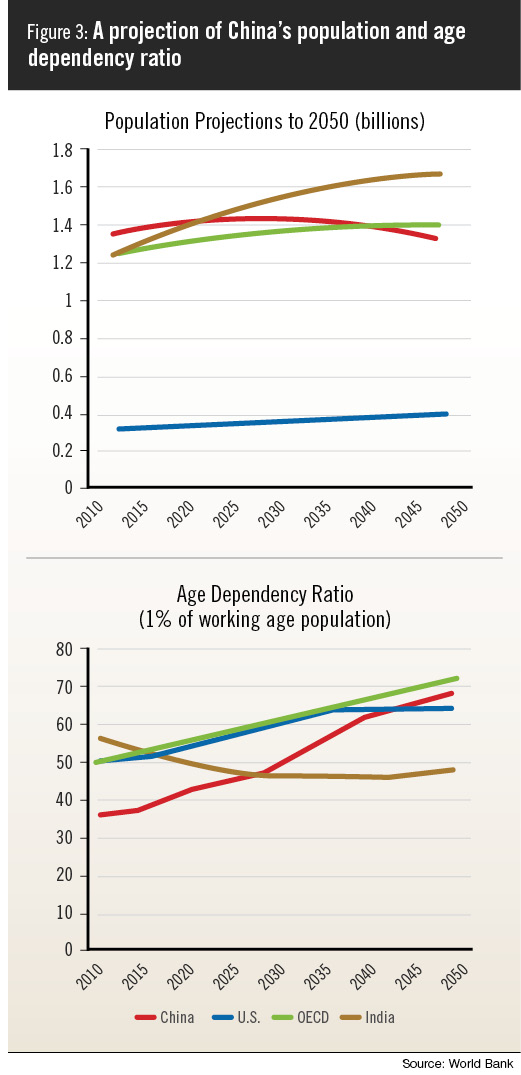

A second limiting factor on China’s growth, and its future, is its demographics. A surprising and direct legacy of China’s draconian population controls (including the “One Child” policy) is that by 2025 China will no longer be the most populous nation on Earth — that honor will go to India, whose growth rate is projected to continue rising until 2050. In fact, by as early as 2030 China’s population will have begun to shrink, being surpassed by the total population of OECD members in 2040 (Figure 3). The very foundations on which China has built its wealth — a manufacturing economy with cheap and plentiful labor, a limitless capacity for economic growth built on the backs of an enormous population — will quickly erode. If the size and growth of global economies remains linked to the youth and size of a nation’s population, then we may soon be asking whether India’s rise is coming at China’s cost.

And the news gets worse; as China’s population shrinks, it also grows older, meaning that a smaller proportion of workers must support the retirement of a larger number of Chinese citizens. This leads to the question of whether China will succeed in growing rich — and moving up the value chain of the global economy — before it grows old.

And the news gets worse; as China’s population shrinks, it also grows older, meaning that a smaller proportion of workers must support the retirement of a larger number of Chinese citizens. This leads to the question of whether China will succeed in growing rich — and moving up the value chain of the global economy — before it grows old.

In turn, China’s political stability continues to depend on the strength and effectiveness of the CCP — a proposition that is likely to be stress tested in a variety of unexpected ways over the decades to come. First, there is the internal stability of the party itself, which may seem monolithic under President Xi Jinping but is far more factional and prone to internal disagreement than it seems. Indeed, Xi’s coronation was almost disrupted when he disappeared for two weeks in September 2012 — an absence, The Washington Post reported, caused when a chair thrown by a senior Chinese leader during a contentious meeting injured Xi when he tried to intervene.

In terms of China’s foreign relations and security, this translates into three key projects that the CCP must advance — deliver Xi’s “China Dream,” stand firm on its geopolitical “must-haves” and avoid conflict as much as possible. China Dream rests on the CCP’s calculation that it has a 20-year window of opportunity in which China can grow rich enough to build a firm foundation for the future of Chinese wealth and power. During this time, the CCP is unlikely to fundamentally challenge the post-World War II economic or political order because most parts of it work in China’s favor for now and it costs China little to maintain. On top of this, China looks to quietly lay the foundations to replicate the CCP’s control of its internal circumstances to control its external circumstances, first economically but eventually politically. One Belt, One Road performs a fundamental task in this transition. While doing this, China must remain firm on its geopolitical must-haves — maintaining the primacy of the CCP in all sectors, maintaining its territorial integrity in Xinjiang and Hong Kong while closing in on Taiwan, and remaining internally postured while deterring outside intervention through an anti-access/area denial military strategy. Lastly, the CCP almost certainly wants to avoid open military conflict with other capable nation states, believing that even small conflicts over issues beyond its geopolitical must-haves will compromise the window of opportunity for the China Dream.

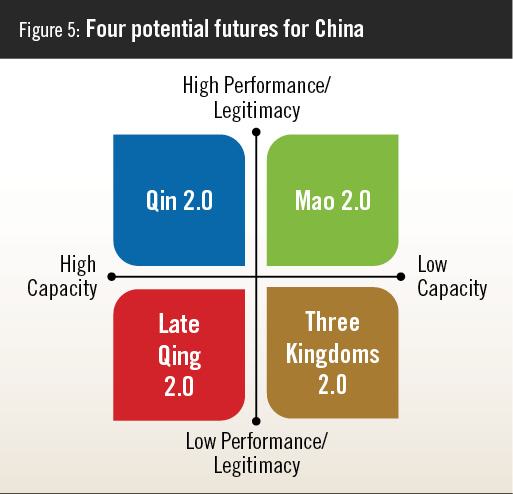

China’s future, therefore, depends on the successful execution of these goals — particularly growing rich before it grows old and evenly distributing the gains. One Belt, One Road is a central means of achieving this. It is also likely that the CCP fears internal threats and instability more than it does outside actors, although it still plans for the latter. Two key factors drive China’s potential futures — whether its economy is running on all cylinders (and is high capacity), and the performance and legitimacy of the CCP. If we arrange these two trends on X and Y axes, we get four interesting potential futures for China (Figure 5).

In a high capacity, high performance/legitimacy future, we get a high-tech repeat of China’s first emperor — a ruling party that uses future tech to tightly control the lives of its populace and its internal security (the “iron grid” of Qin Shi Huang implemented on Chinese life that pinned every subject in their place), while still delivering a rich and comfortable life for the majority of its citizens. In a high capacity, low performance/legitimacy scenario, we get a late-Qing redux — with a booming economy and much wealth being transferred to actors both internal and abroad, but a slow, and then rapid, fracturing of the hold of the CCP, which may lead to a liberalization of Chinese society or a division of the spoils among its most wealthy and influential actors. Alternately, in a high legitimacy/performance, low capacity scenario, we may see a repeat of Chairman Mao Zedong’s repeated attempts to transform China amid bitter circumstances — with the CCP exercising draconian control but to little effect, and with growth stalling and a poor populace seeing global economic progress migrate elsewhere. Finally, the worst of all possible worlds is contemplated in a low performance/legitimacy, low capacity scenario where a return to the instability of China’s Three Kingdoms brings less romance and more collapse.

In a high capacity, high performance/legitimacy future, we get a high-tech repeat of China’s first emperor — a ruling party that uses future tech to tightly control the lives of its populace and its internal security (the “iron grid” of Qin Shi Huang implemented on Chinese life that pinned every subject in their place), while still delivering a rich and comfortable life for the majority of its citizens. In a high capacity, low performance/legitimacy scenario, we get a late-Qing redux — with a booming economy and much wealth being transferred to actors both internal and abroad, but a slow, and then rapid, fracturing of the hold of the CCP, which may lead to a liberalization of Chinese society or a division of the spoils among its most wealthy and influential actors. Alternately, in a high legitimacy/performance, low capacity scenario, we may see a repeat of Chairman Mao Zedong’s repeated attempts to transform China amid bitter circumstances — with the CCP exercising draconian control but to little effect, and with growth stalling and a poor populace seeing global economic progress migrate elsewhere. Finally, the worst of all possible worlds is contemplated in a low performance/legitimacy, low capacity scenario where a return to the instability of China’s Three Kingdoms brings less romance and more collapse.

This simple way of thinking about China’s futures doesn’t predict one or another as more likely; indeed, the truth is likely to be a unique variant on all these scenarios and far more complicated. But it does allow us to envision a number of different states, and then contemplate the place that the success or failure of One Belt, One Road, and China’s relationship with Russia, could have in these different futures.

Potential futures for Russia

In terms of future strategies, it is likely that Russia will attempt to walk a fine line of provocation and concession with the West and bet that European allies won’t have the staying power to commit to a full confrontation or containment policy, and try to extract concessions where they can. At the same time, it would be valuable for Russia to advance its hedging strategies in China and Eurasia, seeking out new markets and allies where possible. Finally, the regime is likely to attempt to strengthen internal resilience and dependency while trying to mitigate the effects of any down times during a resource supercycle. What is most interesting about these strategies is that the three latter objectives seem to intersect directly with One Belt, One Road and the pressing question of whether Russia forms a fundamental part of it. It would not be too far from Sorokin’s future to envision a resurgent Russia that has successfully staved off pressure from the West, forged close economic and security relationships in China and Eurasia, found new markets and means to mitigate its current economic problems, and therefore steadied itself at home.

This leads Russia into an interesting but potentially perilous set of alternate futures (Figure 6). While one of China’s axes of alternate futures rests on the CCP’s effectiveness and authority, in Russia’s case it might be more accurate to pin the trend on the level of dissent within the nation and how that impedes the objectives of Russia’s elites. Similarly, while China’s economic capacity and ability to power the global economy are key questions, for Russia it is a simpler matter of whether it is economically resurgent or depressed. The four scenarios that present themselves are subtly different from China, representing Russia’s different internal structures and sources of strength and vulnerability, but they again have very rough historical analogues. An economically strong and united Russia might present something of Peter the Great 2.0, allowing Russia’s future leaders and elites the scope to challenge or co-opt certain parts of the West while forging a unique relationship and identity in the East (a new treaty of Nerchinsk, or special friendship). The world may have a lot to fear from this geopolitical alignment, and indeed it has been a topic of conversation among crusty old Cold Warriors such as Paul Dibb and Henry Kissinger. An economically strong but politically fractured Russia, on the other hand, might resemble an early Khrushchev period redux in which elites struggle to contain popular dissent while rotating between periods of thaw and crackdown that are not completely within their control. As with China, this would likely lead to a less consistent and more volatile Russia on the world stage, as foreign policy is driven by internal fluctuations. An economically weak Russia with low internal dissent might represent a return to the stagnation of the Brezhnev years, where no one is particularly happy and Russia is withdrawn, but a fear of the potentially far worse prevents drastic action either internally or externally.

And finally, the most feared situation for Russia, would be a return to a period of high dissent and economic collapse represented most potently in the Russian imagination by the transition from Gorbachev to Yeltsin and the years of “shock therapy” to reform the economy. While China’s worst-case scenario represents a collapse of institutions and uncertain transition, it does not necessarily represent the collapse or split of China itself. In Russia’s case, we should not be so certain — given the numerous frozen conflicts (Chechnya, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Donetsk, Crimea) that Russia maintains to solidify its borders and what it perceives as its satellite states. Russia might just split apart under the pressure, simultaneously igniting numerous cold conflicts into hot wars. We may be faced with the reality that the only thing worse than an aggressive and resurgent Russia is one that is collapsing.

And finally, the most feared situation for Russia, would be a return to a period of high dissent and economic collapse represented most potently in the Russian imagination by the transition from Gorbachev to Yeltsin and the years of “shock therapy” to reform the economy. While China’s worst-case scenario represents a collapse of institutions and uncertain transition, it does not necessarily represent the collapse or split of China itself. In Russia’s case, we should not be so certain — given the numerous frozen conflicts (Chechnya, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Donetsk, Crimea) that Russia maintains to solidify its borders and what it perceives as its satellite states. Russia might just split apart under the pressure, simultaneously igniting numerous cold conflicts into hot wars. We may be faced with the reality that the only thing worse than an aggressive and resurgent Russia is one that is collapsing.

One Belt, One Road

Finally, it is worth considering One Belt, One Road and how it might act as a key pivot between these different alternate futures. Specifically, One Belt, One Road was announced in 2013 by Xi as part of his broader China Dream and “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” and the name was changed to the Belt and Road Initiative in 2016. Consisting of $575 billion worth of railways, roads, ports and other projects, it establishes six overland corridors of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road as defined by China. As of March 2019, 125 countries had signed collaboration agreements with China as part of the initiative — although this should be taken with a grain of salt, as the World Bank assesses that only 71 of those 125 economies are in any meaningful way connected to One Belt, One Road. There is also confusion over the Belt-Road part that is worth clarifying: the land routes are “belts” because they allow economic corridors of industry and markets across their length, which will fuel China’s global ambitions, while the “road” routes are sea lanes, which simply convey goods from port to port.

As several commentators have pointed out, China’s economy faces the reality of a slowdown. China must continue its high rates of growth, even with this slowdown, to generate employment and stability. But for many years, the tools of choice for the CCP to do this have been debt and uncompetitive state control. This is no longer likely to deliver the results that the CCP needs. Second, China must rebalance its economy from that of a cheap exports manufacturer to one that supplies higher-value products and services (such as cars, indigenous technology, finance) to internal and external markets. All of this is aimed at avoiding the middle-income trap, or the country growing old before it grows rich.

So far, there are two competing theories of how One Belt, One Road achieves this. The “maximalists,” such as Bruno Maçães, see it as nothing less than the start of an economic new world order presided over by China. Maçães writes that “whoever is able to build and control the infrastructure linking the two ends of Eurasia will rule the world. … By controlling the pace and structure of its investments in developing countries, China could transition much more smoothly to higher value manufacturing and services.” The World Bank has also observed that the “countries that lie along the Belt and Road corridors are ill-served by existing infrastructure — and by a variety of policy gaps. As a result, they under trade by 30 percent and fall short of their potential FDI [foreign direct investment] by 70 percent. One Belt, One Road transport corridors will help in two critical ways — lowering travel times and increasing trade and investment.” Therefore, China is simultaneously filling a gap and building goodwill within the developing world, hoping to lead the next phase of the global economy as it overtakes more developed OECD countries that currently sit atop value chains.

But there is also the “minimalist” theory, arguing that the so far successful publicity campaign elements of One Belt, One Road disguise something that is much less than it seems. For example, Jonathan Hillman, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, argues that the “Belt and Road is so big it is almost impossible for one person to have mastery of it, sometimes I wonder if China grasps the whole thing,” while the World Bank places a large caveat on its previously mentioned analysis. In the same report, the authors argue that the program works “only if China and corridor economies adopt deeper policy reforms that increase transparency, expand trade, improve debt sustainability, and mitigate environmental, social, and corruption risks.” This theory argues that the program is a clever narrative to get more out of what is simply stimulus for the Chinese economy, particularly the construction sector, and that it is a simultaneous marketing pitch to get foreign capital and buy-in for a program that is only going to benefit China. Further, some commentators have highlighted that rather than helping bordering economies, the projects that make up the program are useful debt traps that give China leverage over neighboring governments. Finally, several have highlighted that the program is a useful cloak for the CCP to buy the loyalty of interconnected party cadres and businesses, and that corruption siphons off a good proportion of any investment.

So, which is it? This is a particularly important question, as the program is a key pivot that may decide whether a certain set of China’s or Russia’s alternative futures are more likely than others. And while One Belt, One Road is a huge undertaking that will take many years to assess, so far the picture is not good. It has operated as a debt trap for more vulnerable nations, with Sri Lanka borrowing heavily to invest in new ports but then allowing a state-owned Chinese company a 99-year lease in exchange for debt relief — leaving little for Sri Lanka but setting up a strategic facility for China along its key shipping lanes. The $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor offered a promising demonstration of One Belt, One Road’s potential with a key partner but has been stalled amid Pakistan’s significant debt problems. Burma has scaled back its initial $7.5 billion port deal with China, settling for $1.3 billion, while the Malaysian government has canceled $3 billion worth of pipelines and is threatening to abandon an $11 billion rail deal. The Maldives is seeking debt relief and cancellation due to widespread corruption among its Belt and Road projects, while a power plant in Kenya has been halted by the country’s courts due to corruption and environmental concerns.

Yet One Belt, One Road has scored genuine gains. The World Bank estimates that it has seen trade growth in connected economies of between 2.8% and 9.7% (1.7-6.2% worldwide), while offering significant advantages to China and its trading partners in time-sensitive sectors such as fruit and vegetables or electronics supply. It further estimates that low income countries have seen a 7.6% increase in FDI due to new transport links. But it is also clear that One Belt, One Road is likely to fall well short of the claims of the maximalists; and indeed, placed in historical perspective, this is what we would expect. Against China’s $500 billion of investment, the post-World War II economic order was shaped by the U.S. and its allies with trillions of dollars of investments over decades, including the reconstruction of West Germany and Japan. Simultaneously, scholars are still grappling with the costs the Soviet Union outlaid to build a parallel communist order that eventually collapsed. It was perhaps optimistic to think that China could accomplish a similar epoch-making transformation on the cheap.

An answer

But back to the original question, or at least a variation of it. Does China’s future include Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Iran, Turkey, Europe and Africa? Clearly, the answer is yes. Even if only modest elements of One Belt, One Road are delivered, China will be looking to establish mutually beneficial markets in all these regions — whether it be for resources, food security, new industries or other elements of China’s value chain of production. They simultaneously offer the access, cheap labor, skills and resources that China needs to improve the wealth and satisfaction of its citizens. These markets are close to China, they are amenable to Chinese investment and degrees of control, and they and China stand to gain from the same outcomes.

But does China’s future include Russia? After examining the evidence previously mentioned, while it is possible, on balance the answer is no. And this is for a few overlapping reasons — namely resources, markets, geography, competition and Russia’s outlook. On resources, Russia has a narrow range to offer, mainly energy and natural resources, which China is able to source from a variety of nations closer to its economic arteries than Russia is likely to be. China is not just after supplies, but also a reciprocal market for its value-added goods to ensure a strong two-way trade — Russia is unlikely to provide the latter as it gets smaller and relatively poorer. Despite their treaty of friendship and the construction of an extensive network of pipelines, the inability of Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin to reach a natural gas deal is emblematic of this problem. Related is the issue of markets — Russia is just not a large enough or convenient market for value-added Chinese goods, which tend to bypass it and instead flow to Europe.

Then there is the issue of geography. While images of One Belt, One Road show grand railways traveling through Russia, or perhaps Sorokin’s superhighway, the reality is that unless these “belts” have lucrative markets along the way, shipping remains the cheapest way for China to move goods by an order of magnitude. While the opening up of Arctic shipping may help Russia in the short term, it is simply more cost effective for China to bypass Russia and seek transport (and markets) by other means. Additionally, the World Bank has also pointed out that Russia is not within China’s economic corridor and that the benefits of the program are far likelier to flow to regions like Southeast Asia, Africa and Central Asia. It is also worth bearing in mind that Russia and China remain geopolitical competitors, seeking influence in Central Asia and elsewhere. Both view formal alliances or constraints on their actions warily and would rather decide issues on a case-by-case basis — making anything beyond the rhetoric of a “special relationship” unlikely. Institutions such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and Eurasian Economic Union remain, for Russia-China relations, more akin to forums for discussion than organizations for long-term action, such as the European Union and NATO are.

Finally, there is the issue of Russia’s attitude and disposition more broadly (as well as that of China’s). Despite having loose, common grievances against the West, it is unlikely that relations would be any easier with China in the driver’s seat. Russia likely would have the same problem it has with the West — resentment at not being treated as an equal. This is fundamentally because it isn’t one and certainly is not going to gain in stature to 2050, given the trends previously mentioned. Under a Chinese new order, China would be even more likely to actively pursue its interests and ignore Russian ones. Russia might even grow wistful and miss its old geopolitical competitors in the occident.

Potential strategies

But futures analysts must consider a range of alternate futures. If China and Russia do grow closer, what might be the West’s options? Four strategies to deal with Russia, and forestall China, present themselves: A new “Marshall Plan”; “self-strengthening” under China; integrating Russia; or confronting and isolating (… forever).

A new Marshall Plan — option one — would entail the U.S., its allies and partners competing with One Belt, One Road by offering developing nations, and those China is trying to capture, access to other markets and opportunities. This would entail spending a great deal on infrastructure, investments and other development projects. It would be nation building for new markets, creating an alternative to China and opening more attractive opportunities to countries in Southeast Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Different nations could specialize in niches of the global economy (something Japan tried in South and East Asia in the 1990s). It would be a big, expensive plan with all the drawbacks that come with a project of that size. This would require a huge amount of coordination and agreement, which Russia and China would try to undermine at every opportunity. Yet, there are precedents — the EU, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, the work of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. But have the days of George C. Marshall, Franklin D. Roosevelt, reconstruction and nation building come to an end?

Option two would be self-strengthening under China, a phenomenon the Chinese are intimately familiar with. Following the reign of unpopular but powerful emperors, or even lower-level, corrupt officials, actors would simply bide their time and gather what resources they could while avoiding the pitfalls of the regime. This could involve the West letting China take the lead under One Belt, One Road, working out where it can be used to its advantage, and making what profits it can while the going is good. Developed nations could integrate into China’s supply chain, offer opportunities for Chinese investment and smooth the way for China (e.g., via World Trade Organization market economy status). This would also entail accepting Chinese-mandated limits on political speech and the interventions that nations could engage in — for example, criticizing China’s human rights abuses or protecting the status of Taiwan. Indeed, Facebook, Google, Disney and other companies have already shown a willingness to engage in exactly this sort of self-strengthening (with some hitches) and may be willing to do more. The recent National Basketball Association controversy in China shows what this would entail — the opportunity to make billions in Chinese markets, but no room for negative tweets about China’s actions in Hong Kong. But are we willing to pay this price?

A third option would be the most drastic — avoiding a close relationship between Russia and China by reintegrating Russia into Europe and into the global community. Given Russia’s recent adventurism and delinquency, this may be a hard option to embrace. But it would isolate China as the only major holdout to the post-World War II international order. Allowing Russia back into the club would allow the West to make use of its influence in Central Asia and the Middle East to shut out China from its main One Belt, One Road objectives. It would involve negotiating an end to current Russian hostilities and outsider status (almost certainly to the disadvantage of Ukraine) and let Russia achieve the European integration it hoped for prior to 2008. The U.S. and its allies would have to accept a Russian sphere of influence, as well as the Russian way of doing business within it, and possibly in the rest of Europe (a way which generally involves petro-politics and varying degrees of corruption or gray-zone legality). This would incentivize Russia and its dependencies to work with the West, while closing out China, almost in a mirror image of Nixon’s 1972 opening to China. But can we live forever with Russia as it is now? And can we sell important allies short to achieve it?

The final option would be to continue our current approach, now and forever. This would continue the strategy of profiting off China and Russia where we can while reducing dependency — and confronting them strongly on nonnegotiable issues. It would push China and Russia to bend to the post-World War II consensus, while acknowledging that this is likely to have limited success. It would continue to turn economic problems (One Belt, One Road) into security problems (a parallel system, and therefore a base of Chinese power). The U.S. and its allies would have to advance significantly into gray-zone and hybrid warfare to counter Russian and Chinese below-the-threshold operations. It would entail the creation of parallel economic and political systems, while pushing nations in between the two blocks to pick sides. Ultimately, it would contemplate complete economic decoupling and deinvestment from China and Russia, potentially leading to Chinese instability and Russian collapse. But the question remains, what would be the desired end state of this strategy?

Conclusion

There is no obvious reason to believe that a close Russia-China relationship is more likely than their current relationship of convenience and occasional strategic alliance. Yet, it is useful to contemplate, and attempting to formulate responses to a range of alternate futures allows us to expand our thinking and the realm of the strategically possible. Several things are clear — we must think carefully about what our preferred future might be, consider the range of scenarios and how we might respond to them to get there, and keep a sharp eye out for indicators that will signal in which direction events are heading.

Andrei Danilovich Komiaga may not get his desired comeuppance for the complacent gentlemen of Nice, but achieving a better future than the dystopia Sorokin envisions will require a great deal of planning, forethought, futures analysis and smart strategy from us and from our future leaders.

Comments are closed.