Adjusting to a New International Dynamic

By Małgorzata Jankowska, counselor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland | Photos by AFP/Getty Images

We are in a new era of great power competition, with the United States, China and Russia as the main competitors. This perception is widely accepted by scholars and politicians across the world. It has been unsettling regions and countries, which have functioned for some time within the rather clear rules of a U.S.-led international order. The ongoing adjustment seems to have particularly profound implications for the West. The feeling of existential change is acute in the European Union and its de facto leader Germany, which have benefited and prospered well under the so-called Pax Americana.

Faced with the competition between the U.S. and China, European leaders have been calling for unity and mobilization at the European level. Some argue that a strong and sovereign Europe is needed to defend the existing order; otherwise there will be no Europe at all. Speeches by French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier warn that Europe will become the prey of the great powers.

Indeed, Europe must position itself within this new international dynamic. How Europe will manage this process and what will be its future shape depends a great deal on the direction Germany takes. The EU needs Germany because it is the biggest member state, has the largest economy and anchors the euro. But more importantly, Germany needs Europe. Its national interests are embedded within the interests of Europe, and the EU and its institutional framework. As Steinmeier put it, Europe is an indispensable framework for Germany to assert itself in the world.

The Visegrád countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary), or the V4, are a good place to look at how great power competition plays out in Europe. For security, the V4 depend on active U.S. engagement and presence in Europe. However, in terms of development and economy, Germany plays a dominant role. Interestingly, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, while visiting Hungary, Slovakia and Poland in February 2019, talked about a vacuum in the region that Russia and China are ready to fill. In fact, despite joining NATO more than 20 years ago and the EU 15 years ago, the region remains on a fault line between the West and the East. Berlin’s response to great power inroads in its own geopolitical neighborhood may provide insight into the future shape of Europe.

The rise of China

Over the past several years, the EU has become more concerned with its own vulnerabilities, vis-à-vis China, in areas in which it has traditionally had the upper hand. European companies have not only been losing out in competition with Chinese companies, but the EU’s institutional setup has appeared ill-equipped to deal with a state actively using unorthodox instruments, including coercion, theft and state-run industrial espionage to expand its global economic presence. In addition, Beijing seriously exposed the limits of the EU political agenda, especially with respect to human rights. Beijing has not only defied pressure from Brussels, it has been actively promoting its own vision of human rights. And in claiming to lift millions of people out of poverty, it also gained the attention of other developing countries.

With the ascent of President Xi Jinping to power in 2012, China has become more eager to wield its economic and political clout globally, including in the EU, as well as in its own backyard. In 2012 in Warsaw, China launched a platform of cooperation with 16 Central and Eastern European countries called 16+1 and that included the V4 states (since Greece joined in 2019, the platform has been called 17+1). This Chinese economic overture appeared at an opportune moment. Following the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent, significant drop in Western foreign direct investment (FDI), Central and Eastern European states struggled to find sources of financing, other than EU funds, to fuel economic growth. Business and political elites saw China as an important partner in addressing and overcoming this shortfall, and as a driver to help modernize and stimulate economic growth in the region. In addition, at that time, cooperation with China was generally seen as positive and Chinese assistance during the euro crisis was duly recognized in Brussels, and so should have been Beijing’s pledge to create a credit line for the 16 countries worth $10 billion.

The initiative, however, raised immediate alarm in Brussels and Berlin that China would use financial and economic pressure on the EU member states in the 16+1 to influence the decision-making process within the EU and undermine the block’s cohesion and unity. European officials argued that countries in the region are still too weak in terms of governance, rule of law and transparency, and that Chinese influence could lead to the erosion there of EU norms and values.

At the same time, Chinese investment in Central and Eastern Europe has been presented as being of substandard quality, not meeting EU standards. However, if analyzed against economic data and political relevance, those arguments are hardly justified. The Mercator Institute for China Studies, which regularly publishes reports on Chinese economic activity in Europe, noted in a 2019 paper that “the ‘Big Three’ EU economies received the lion’s share of [Chinese] investment,” namely Germany, France and the United Kingdom, while investment in Central and Eastern Europe has declined. The big three also remain China’s main trading partners in Europe. As for political influence, no Central or Eastern European country went so far as to welcome China’s support for reforming the EU, as Macron did in 2019.

Germany remains vocally opposed to what is now the 17+1 platform, which is, in fact, a recurring topic at high-level discussions between Chinese and German officials, including during the frequent meetings Merkel holds with her Chinese counterparts. In 2017, then-German Minister of Foreign Affairs Sigmar Gabriel went so far as to request that Beijing “pursue a one-Europe policy” and not try to divide Europe, comparing it with the EU’s One-China policy with regard to Taiwan. China protested, insisting that Taiwan is a part of China, whereas the EU is composed of sovereign states. In a 2017 article, Cui Hongjian, director of the Department of European Studies at the China Institute of International Studies, a think tank linked to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, pointed out that Germany cannot afford to lose its preeminent place within the European division of labor, in which Central and Eastern European production plays a key role. In fact, the Visegrád countries are key participants in the European automotive production chain.

From this perspective, Germany must apply all means of pressure, incentives and even disciplinary measures to discourage any initiative involving China that would enable V4 countries to pursue their own interests independent of Brussels and Berlin. Potential access to Chinese financing is of particular sensitivity; Beijing could potentially provide an alternative source of financing and investment to a region that is dependent for its economic growth on funding from the EU and FDI from Western Europe (mainly Germany). In 2011, Beijing bought Hungarian government bonds, providing alternative financing at a time when Budapest struggled with the fallout from the financial crisis and was under huge pressure to accept International Monetary Fund assistance.

Unable to ignore Chinese overtures, Germany insisted that China not undermine Germany’s economic standing in Europe and globally. Managing 17+1 has been a kind of testing area for establishing a framework of European-Chinese cooperation in other countries. Finding a proper arrangement at this early stage has been essential, given growing Chinese engagement under One Belt, One Road in Africa, Russia and the Middle East.

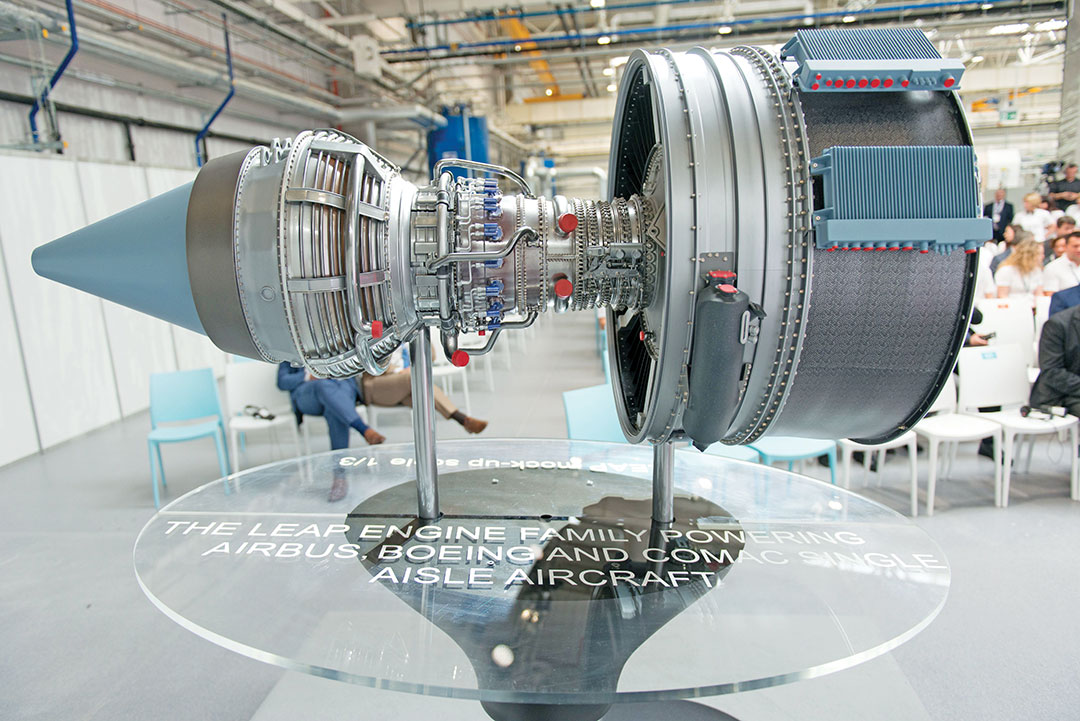

Another wake-up call was the acquisition by a Chinese company of shares of German robotics maker KUKA, a company in a high-end manufacturing sector. It draws attention to a pattern of Chinese foreign investment in Europe focused on critical infrastructure and advanced technologies, and aligns with Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” policy, a blueprint for transitioning to the production of higher-value products and services. In addition, European countries, especially Germany and France, have realized that in terms of new technologies such as 5G and artificial intelligence, Europe is so far behind the U.S. and China that it risks becoming a rule taker, and no longer a rule maker.

This feeling of losing ground is particularly acute in Germany, which has built its predominant economic position in the EU and its global standing on being an export-oriented industrial powerhouse. The “China factor” has become a driving force of intra-European transformation. The Federation of German Industries policy paper of January 2019 and the EU’s joint paper, “EU-China Strategic Outlook,” of March 2019 reflected the same concerns: Both papers defined China as a systemic rival — a stark departure from standard EU language. The EU document proposed 10 actions to improve the EU’s standing regarding Beijing. Some of them, such as calls to reform EU competition policy, investment screening mechanisms or rules on international procurement, have direct implications on the functioning of the single market, blurring the line between internal and external EU policy. Together with the “Franco-German Manifesto for a European industrial policy fit for the 21st Century,” issued in February 2019, the papers serve as a mobilizing tool to impress on other EU member states that a comprehensive overhaul of EU institutions and mechanisms is required to deal with a new international landscape.

Germany’s decision to host during its EU presidency an ad-hoc EU27 summit with China in September 2020, irrespective of the EU’s plan for a proper EU-China summit in the first half of the year, is proof that such an overhaul is needed. The spread of the coronavirus forced German authorities to change their plans; however, the decision is a step back to pre-Lisbon Treaty practice and definitely undermines EU institutions.

For the V4, the economic implications of China’s rise are different. They are striving to overcome a development gap compared to the core European countries. China is of limited importance in achieving this goal, compared to Germany, which is the main trading partner for all four countries. It is also the main investor. Some argue that the V4 region is so embedded in the German economic space that it amounts to a kind of ecosystem. V4 leaders emphasize that the four countries together have become Berlin’s No. 1 partner, surpassing France and ahead of Moscow. In 2019, when signing a declaration on Polish-German cooperation, Jadwiga Emilewicz, then Poland’s minister of entrepreneurship and technology, explained that the two economies are highly complementary, with Poles offering innovative ideas and qualified employees and Germans primarily capital and experience. Arguably this model of cooperation is also true regarding the other V4 countries.

The V4 countries are aware of the risks associated with the middle-income trap. This dilemma is particularly felt in Poland, the largest economy and the biggest country in the region. On one hand, Poland joined those EU countries uncomfortable with the Franco-German call to overhaul existing mechanisms and procedures and insisted that the full implementation of the single market is not only required but is also “a source of growth and opportunities for citizens and businesses.” On the other hand, the Polish government recently joined Germany, France and Italy in their call to adapt the EU competition framework and devise an adequate European industrial strategy allowing EU companies to compete globally.

Poland is not unique in pursuing such a constructive ambiguity. Even Germany is torn between those who advocate changes and those who would prefer to adhere to old procedures and rules. The point now is to determine whether and to what extent policies proposed and pushed at the European level in response to China’s challenges are conducive to V4 development goals. To what extent do they address the development gap, and to what extent preserve the existing division of labor? There is a difference between dependency and interdependency, and delays in intra-European integration and cohesiveness will continue to be the source of internal tensions.

Shifts in the trans-Atlantic community

Faced with formidable challenges from China and less predictable U.S. leadership, German leaders seem to have concluded that they must take responsibility for their own development and security. This is an uneasy situation for Berlin since the institutional setup of the EU, with security provided by the U.S. and NATO, amplifies Berlin’s political influence and strength. German and European political, security and strategic interests have become, to a certain extent, interchangeable, despite difficult political questions deriving from past conflicts, such as the two world wars. Aware of its own limits, as well as the historical implications, Berlin is cautious in responding to French initiatives in the security domain. In one sense, Berlin is in a weaker position compared to France, which holds a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, has its own (however limited) nuclear capacity and is used to sending troops abroad on military missions.

However, Berlin’s engagement in the European Defense Union and its support for developing the EU’s strategic culture are growing steadily. Steinmeier concluded at the 2020 Munich Security Conference that with Pax Americana in question and the U.S. administration seemingly skeptical of the EU, Berlin is ready to seriously engage in building the European Security and Defence Union — but as a strong, European pillar of NATO. Reticent in talking about European strategic sovereignty, Berlin argues that a strong European pillar of NATO will make Europe a more attractive partner at a time when U.S. priorities lie in Asia. The message is intended to reassure those who still value the trans-Atlantic community as the best security framework for Europe. Berlin also recognizes that the concerns and fears of the V4 need to be taken into consideration. Actually, the V4 countries, irrespective of their politics, expect Germany to assume more responsibility in defense and security. Arguably, then-Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Radosław Sikorski was speaking for many when, in 2011, he confessed to fearing German power less than German inactivity. Those expectations are echoed in current calls, including from the V4, for Germany to engage more by spending 2% of its gross domestic product on defense and security.

However, it is an open question what a strong European pillar of NATO may imply for V4 security. For the V4 countries, their unpredictable and unstable neighborhood, to a great extent the result of Russia’s destabilizing policies, is the main concern. Each may differ in their approach toward Russia at the tactical level. However, they all agree on the strategic priority of maintaining credible NATO deterrence capabilities, which cannot be achieved without the U.S. This is why the leaders of Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary joined the Polish-Romanian Initiative (The Bucharest 9 Initiative) to actively promote stronger engagement by the U.S. and NATO on NATO’s eastern flank. For the V4, the U.S.’ presence, engagement and interest in Europe is a key issue.

Berlin’s decision to move forward with the Nord Stream II natural gas pipeline from Russia to Germany points to a possible cleavage. The perception of the Russian threat and how to address it differs: For Berlin, Nord Stream is an economic project; for the U.S. and the V4, there are serious security implications. Faced with Russia’s destabilizing policies, the V4 countries have expected, first and foremost, solidarity from their main European partner. Recent calls from both Paris and Berlin to engage Moscow and develop what Steinmeier recently called a truly European policy on Russia are not reassuring, especially since the gap between Europe and the U.S. has been growing.

In the Visegrád countries, there is limited appreciation for a sovereign Europe that wants to engage globally, but put Washington, Moscow and Beijing all in the same category of partners. For the region, it is important to strengthen NATO and the trans-Atlantic community, and differences between the U.S. and Europe are considered of the second or third order of magnitude. From this perspective, some steps taken by Berlin, Paris and Brussels are seen as conducive to the strategic objectives of Russia and China — mainly, to undermine the U.S. as a global power. Despite its pledges, without a strong trans-Atlantic framework, Europe will not be able to sustain the existing international order. This tension was perceptible at the 2020 Munich Conference. In the face of global challenges, the presidents of France and Germany called for more European engagement and unity, whereas Slovakian President Zuzana Čaputová stressed the importance of values that undergird the West and are shared across the Atlantic.

Conclusions

Germany may perceive its role as that of a political power organizing Europe in an era of great power competition. What is remarkable and revealing is not that Germany is prepared to play a leading strategic role — because of necessity or opportunity — but that it is determined to pursue maintaining the current international order with or without the U.S. and, if needed, by altering the way the EU functions. A key, long-term and self-benefiting strategic priority for Berlin is to have a strong Europe. That means that, first and foremost, Europe must be united, with Germany willing to assume responsibility for achieving that goal. Coming from the biggest EU member state, this may be a framework to legitimize its dominant power. Instead of unity, the Visegrád 4 are calling for solidarity.

The difference points to an underlying tension. The V4 countries are aware that big states bear a greater responsibility and, therefore, have a bigger say in the decision-making process. However, they fear that calls for unity may lead to uniformity and the leading powers making decisions on behalf of others. Decades ago, Henry Kissinger asked, “Who do I call if I want to call Europe?” But in his latest book, The World Order, he asks, “How much diversity must Europe preserve to achieve a meaningful unity?” The V4 countriesʼ perspectives on great power dynamics are helpful in grasping to what extent the ongoing shifts in the international order may bring a qualitative change in the political, economic and institutional setup of Europe.

Editor’s note: This article was written before knowing the full impact of the coronavirus pandemic on social, economic and political life across Europe and the U.S.

Comments are closed.