A Hybrid State Unbounded by Limitations

By Col. Ryan L. Worthan, U.S. Army

NATO’s final communique from the 2016 Warsaw summit recognized the changed security environment in which Russia’s malign “activities and policies have reduced stability and security” and “increased unpredictability,” requiring enhancement of its “deterrence and defence posture.” Collectively, NATO has broadened its deterrent approach, encompassing a whole-of-government strategy and providing measures of reassurance and deterrence by bolstering military presence, partner capacity, interoperability and alliance resilience. The ongoing sanctions regime complements NATO’s efforts by constraining the resources and mobility of select Russian individuals and businesses. This complementary approach seeks to influence Russia as a unitary state without substantively dissuading the nonstate actors (NSA) Moscow uses to shape the environment and undercut regional stability.

NATO’s deterrent concept is premised on the assumption that Russia operates as a unitary state and is therefore capable of being deterred according to the tried and tested principles and assumptions embedded in rational deterrence theory. Likewise, the preponderance of contemporary Russian deterrence literature focuses on the threats and potential responses to hybrid aggression conducted by a unitary state in the nebulous space between peace and war. Russia is undoubtedly a unitary state under President Vladimir Putin, but the duality of traditional state organs and a networked patronal power structure unbounded by unitary state limitations provides Putin a broad menu of means and methods to attain strategic objectives. Bureaucratic pluralism and hybridity of associations challenge conventional deterrence thinking and call into question Moscow’s evolving decision-making apparatus and risk calculus. As the Marshall Center’s Graeme Herd puts it, Russia’s ongoing trend of “de-globalization, de-institutionalization, and de-modernization” make it dependent upon the tools and methods employed by NSAs to exert influence abroad. Russia’s weak formal institutions are increasingly influenced and often controlled by an underlying network of patronal power centers shaping Russia’s strategic agenda. These trends suggest a more basic set of questions be answered regarding Russia: Is Russia a unitary state actor, or has it morphed into a hybrid state? And what does that mean with respect to deterrence?

To deter a nuclear armed, conventionally capable hybrid state actor (HSA), NATO must develop a strategy to concurrently deter the state while compelling its attendant NSAs. NATO must maintain the nuclear deterrent, continue its support of forward resilience measures and reinforce conventional defensive arrangements to deny Russian objectives, while enabling individual nations with the requisite knowledge, capabilities and capacity to deny and, if necessary, locally punish Russian malign actors.

Unitary State vs. NSA Deterrence

Rational deterrence theory argues the “balance of deterrence” leads to stability and status quo maintenance. It assumes unitary state actors approach strategic decision-making in a logical manner, pursuing outcomes through rational cost-benefit analysis. At its core, the purpose of deterrence is to dissuade a potential aggressor from taking unwanted actions by shaping the aggressor’s perception of the defender’s political commitment to respond, the aggressor’s decision-making processes, and the aggressor’s ability to accurately calculate and control risk. As Daniel Sobelman noted in his study, “Learning to Deter,” “deterrence is achieved through the communication of calculated credible threats designed to shape or reshape the perception and manipulate the behavior of another actor.” “Deterrence by punishment” and “deterrence by denial” are the most often applied methods. In the nuclear realm, the costs of a challenge to the status quo are both clear and high. But as Alexander L. George and Richard Smoke note in Deterrence in American Foreign Policy: Theory and Practice, in the conventional military realm, deterrence by denial attempts to shape an aggressor’s perception that the costs and risks of an aggressive act outweigh the expected benefits. Successful deterrence maintains the status quo by removing aggressor options through denial or threat of punishment, but the initiator’s possession of an increasing variety of options requires that deterrence thinking evolve or risk failure.

Deterring unitary states employing all elements of national power is challenging but widely researched and well-documented. Deterrence of NSAs is less studied and complicated by asymmetries of political will, strategic objectives, centers of gravity, operational approaches, organizational structures and political resolve, making deterrence difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

The most studied NSAs accomplish their objectives through violence. But NSAs span licit and illicit organizations, mobilizing populations, resources and ideologies regionally and transnationally. The confluence of ideological movements, proliferation of technology, and increased access to finance and information make NSAs increasingly influential and “drivers of state action,” as recognized by Anne-Marie Slaughter in The Chessboard and the Web: Strategies of Connection in a Networked World. While NSAs lack traditional state power, they nonetheless achieve influence by leveraging relative strength disparities, which are often intensified by patron-proxy relationships. Furthermore, the NSA’s ability to exploit differing rules provides opportunities that enable relatively weak NSAs to compete, coerce, deter and often prevail against stronger state adversaries. Sobelman’s study of the Israel-Hezbollah conflict highlights how a state and an NSA achieved deterrence by fulfilling the core requirements of communication, capabilities, credibility and resolve. While Hezbollah exploited asymmetry to compete with the Israeli state, Israel adapted its deterrent construct to blend the negative, defensive and static characteristics of deterrence with the positive, offensive, overt and dynamic characteristics of compellence. Ultimately, an NSA exploited asymmetry to deter a state, and the state’s adapted strategic approach reverted the conflict to a symmetric framework.

While NSAs lack unitary state power, their very asymmetry makes them inherently resilient, and those possessing patron support are significantly more challenging because they are unhindered by the patron’s need for populace support, are often unencumbered by the restraints of international law and unconcerned with the legitimacy of their actions. The ideological sources of NSA resolve, decentralized operational approach and networked structures pose stark challenges to conventional deterrence due to the challenges of holding NSA interests at risk, often requiring coercion or compellence by force. Short of military action, states must compel NSA behavior change by imposing unsustainable costs to NSA interests. Successful compellence offers the NSA no choice but to change behavior, making them strategically irrelevant.

The Hybrid State: Reframing Russia

While unitary state deterrence is well documented, and the Israel-Hezbollah conflict provides insights into NSA deterrence, the concept of a hybrid state is largely unconceptualized and, therefore, deterring one is generally unconsidered. However, the emergence of the hybrid state is already changing the character of conflict.

States adapt and evolve through experiential learning and structural change. Learning facilitates improved capacity and effectiveness, while structural change broadens capabilities and resilience. Relatively weak patron-supported NSAs may attain regional effects, but external dependency exposes exploitable vulnerabilities, making compellence and coercion possible. Regional powers deliberately harnessing state resources to support or create NSAs gain a unique ability to broaden capabilities, bolster resilience and maintain deniability. The concept of state-created NSAs is not historically unique, as evidenced by a letter from 1921 between the British foreign secretary and the Soviet commissar for foreign affairs: “When the Russian government desire[s] to take some action more than usually repugnant to [the] normal international law of comity, they ordinarily erect some ostensibly independent authority to take action on their behalf. … The process is familiar and has ceased to beguile.” Deliberate proxy creation allows for actor and intent ambiguity, requiring that the state and its NSA-like subsidiaries be addressed simultaneously to achieve deterrent effects.

Putin’s centralization of power reinforces a patronal power structure reminiscent of the Soviet era, but devoid of Soviet ideology or its associated institutions. Richard Sakwa’s dual-state model advanced the concept of a constitutional state functioning separately from the dominant power system. The Russian regime exists at the center of a shifting constellation of patronal power centers, operating outside the legal framework of the normative state. Though writing about Ukraine, Andreas Umland posited that power within a patronal system is accumulated and exercised through distinctly informal relationships between elites occupying positions of power in economic conglomerates, regional political machines and official government posts. The most powerful patronal networks penetrate every aspect of Russian society, ranging from ministries and political parties to economic conglomerates, media outlets and nongovernmental organizations. Herd describes a “Collective Putin” concept in which Putin balances the power and influence of three distinct pillars: the normative state; parastatal economic, political and social entities; and nonstate oligarchic actors. In an article for the website Open Democracy, Umland describes the glue holding these networks together as an assortment of “familial ties, personal relationships, long-term acquaintances, informal transactions, mafia-like behavior codes, accumulated obligations, and withheld compromising materials, or kompromat.” Putin exercises power through a network of functional, regional and local kurators who facilitate the “exchange of posts, money, real estate, goods, services, licenses, grants and favors.” These unofficial networks influence, if not covertly direct, Russian policy and decision-making. The “collective Putin” reaps the benefits of power while remaining immune to the constraints, obligations and responsibilities inherent to traditional governance postings.

Through this dichotomy of national character and power, Russia embodies the hybrid state paradigm. The HSA actively combines the benefits of unitary state legitimacy with NSA freedom of action, internally reinforcing and benefiting the elite, while affording supplementary capabilities with which to shape the strategic environment. The very nature of a patrimonial power network encourages elite participation in enterprises and activities that blur the lines between licit and illicit, formal and informal, public and private, foreign and domestic. Active and direct oligarch and siloviki (those associated with the security services) participation in Russia’s shaping operations create a challenge, which Mark Galeotti characterizes in “Russia’s Hybrid War as a Byproduct of a Hybrid State,” as “complex, multi faceted, and inevitably difficult for Western agencies to comprehend, let alone counter.” It is this combination of decision-making ambiguity and deniable action upon which maskirovka, or strategic deception, is built.

Maskirovka underpins Moscow’s pursuit of strategic advantage and its ability to successfully operationalize deterrence-challenging typologies: controlled pressure, limited probes or faits accomplis. Nuanced application of subconventional methods executed by intermediaries affords the Kremlin deniability while obscuring operational intent. While the West traditionally views economic sanctions and diplomatic pressure as levers to prevent conflict, Russia views them as measures of war itself. Beyond Russia’s view of traditional great power interactions, Galeotti highlights Putin’s “ʻtotal warʼ approach to governance: the absence of legal, ethical and practical limitations on the state’s capacity openly or covertly to co-opt other institutions to its own ends.” Putin leverages the hybridity of the Russian state to weaponize every asset to play great power games without great power resources, effectively waging a political struggle with the West through political subversion, economic penetration and disinformation.

Moscow’s strategic objectives are widely accepted to be: regime protection, expansion of its near-abroad influence, weakening of Western states and alliances, and reinstatement of a multipolar world. However, understanding its priorities requires a functional understanding of patronal power networks. Putin’s crucial prerequisite for preserving power rests on his ability to maintain broad public support and apparent electoral success, but he is beholden to a network of actors who facilitate the criminal corruption schemes constituting the core and purpose of much of post-Soviet patronal politics. While Russia’s strategic objectives are clear, regime protection is paramount, with all other objectives feeding that singular end.

Understanding the Hybrid State

To better understand the uniqueness of the hybrid state as an entity, it is helpful to explore the differences between centralized, decentralized, and hybrid organizations, which is described by Ori Brafman and Rod A. Beckstrom in their book, The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations. Centralized organizations have clear leadership and formal hierarchy, using command and control to keep order, maintain efficiency and conduct routine business, making them effective at management and task accomplishment, but inelastic and susceptible to system shocks. By comparison, decentralized organizations lack a clear leader and distribute power across the system, making them resilient and resistant to system shock, but often inefficient at task accomplishment. The hybrid state incorporates the hierarchical leadership necessary for system control and task accomplishment while harnessing the initiative, intellect and resources of the collective to innovate and create opportunities. Brafman and Beckstrom’s analysis of hybridized business structures provides insight to Putin’s organizational preferences and the techniques he employs to attain strategic options and advantages. Putin’s patronal network is effectively a decentralized system composed of autonomous business units, adhering to a set of rules and norms, accountable for producing results in the form of profit, effects, or both. This approach maximizes strategic opportunities while maintaining strong directive ties to preserve veto authority.

Putin maintains considerable, but not absolute, veto authority over the activities of a loose network of actors holding formal government posts and guiding informal factions conventionally labeled by Richard Sakwa in “The Dual State in Russia,” as the siloviki, the “democratic-statists” and the “liberal-technocrats.” The U.S. Treasury Department’s January 29, 2018, “Kremlin Report” identifies a similar set of influence groups: senior political figures holding official government postings, heads of large state-owned parastatal enterprises and oligarchs. Those listed in the “Kremlin Report” are not uniformly subject to the legal rules of the normative state, allowing some the latitude to rapidly adapt to circumvent constraints and maximize opportunities. Recognizing this challenge, the Treasury Department’s sanctions of April 6, 2018, sought to deter Russia by targeting “a number of individuals [and entities] … who benefit from the Putin regime and play a key role in advancing Russia’s malign activities.” These sanctions indicate a refined organizational appreciation, but successful deterrence will also require the West to understand how Putin exercises power and the degree to which the networked, patrimonial Collective Putin influences strategic decision-making.

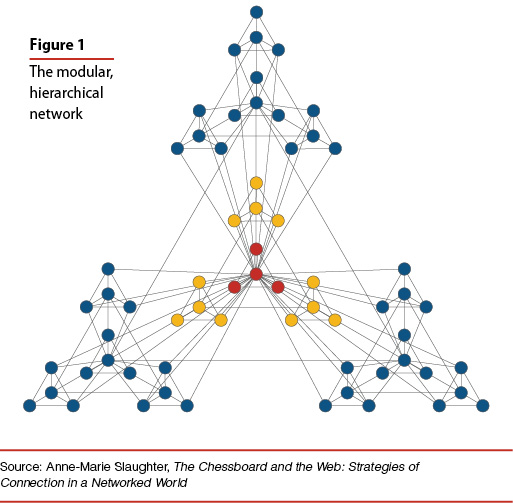

Anne-Marie Slaughter noted that “the traditional definition of power rests on the ability to achieve your goals either on your own or by getting someone … to do what you want them to do that they would not otherwise do.” Hierarchical organizations traditionally view power through a transactional or coercive mindset, while networked organizations acquire and manage power through the volume and strength of connections between network nodes. Putin’s governance structure internally employs the hard power of coercion and the soft power of attraction through a mixture of command, agenda-setting and preference-shaping strategies. While the patronal system is predicated on positional and coercive power, it is strengthened by a network mindset where information, communication and material flow between network actors. The modular hierarchical network model from Slaughter’s book provides a viable characterization of what a network model of the contemporary Russian state would look like [Figure 1]. A central node connected to other nodes in a descending hierarchy of centrality and connectedness; everyone is connected but not for every purpose, creating system resilience through a combination of nodal diversity, modularity and redundancy. Taking from Galeotti’s article “Controlling Chaos: How Russia Manages its Political War in Europe,” the presidential administration represents the central node “and perhaps the most important single organ within Russia’s highly de-institutionalized state.” While the presidential administration holds a central network position, the underlying patronal system necessitates Putin’s personal arbitration of interagency conflict and involvement in decisions of strategic significance.

Putin’s ability to build, gatekeep, adapt and scale his patronal network operationalizes Joseph Nye and Suzanne Nossel’s concept of “smart power.” Putin blends elements of hard and soft power through the selective employment of every tool available to leverage influence across a grid of allies, institutions and corporations, maintaining internal stability while achieving strategic objectives. Russia’s employment of smart power and maskirovka make a fitting national strategy, given a convergence of Russian history steeped in patrimonial power networks, burgeoning NSA influence, the ambiguity and deniability necessary to compete when constrained by a lack of soft power, and challenging demographic and economic conditions.

Harmonizing of Deterrence and Compellence

Harmonizing of Deterrence and Compellence

Putin’s hybridization of the Russian state began the day then-President Boris Yeltsin appointed him prime minister and granted him the authority to coordinate all power structures. But Putin’s power structure is not vertical in a dictatorial sense, rather, it is an adaptable construct which he balances based on his central role as arbiter and moderator of the switching functions between competing patronal groups. His overarching objective is regime protection, but the objectives of the patronal conglomerate vary. Putin’s fulfillment of the disparate objectives of critical network nodes preserves internal stability while affording him access to a wide array of conglomerate-generated, subconventional effects for internal and external use.

The structural changes Putin has put in place have moved the character of Russian governance along a continuum from unitary to hybrid state, generating strength, but also creating exploitable vulnerabilities. The strength and weakness of Putin’s hybrid state springs from nodal interdependencies — the ability of individual nodes to obtain their objectives by generating purpose-fulfilling value, or effects, for the network. The Collective Putin is principally a business network built upon mutual-trust relationships, fueled by the exchange of power, resources and information brokered by kurators, who gatekeep and manage the connections between different networks. The factors that maintain elite cohesion and the power of Putin’s kurators are also the primary network vulnerability, in the sense that removing highly interconnected nodes can damage or even destroy the entire network. Exploiting Putin’s network vulnerabilities, and therefore shaping the perceptions of Russia’s NSAs, demands that the West embrace a more offensive, overt and dynamic compellence construct to complement ongoing deterrence efforts.

If the purpose of deterrence is to dissuade unwanted action, the West must view Russia not as a mirror-imaged unitary state, but as a hybrid state. Hybrid state deterrence requires the simultaneous deterrence of the normative state and compellence of the networked actors who guide, support, and finance its nonstate entities. Deterring an HSA therefore requires dedicated focus, persistence and analytical rigor to map the network, its players, their relationships and objectives, and the opportunities inferred by emergent vulnerabilities. Inadequate network understanding will inadvertently inform actions that produce incomplete network disruption and allow rapid reconstitution of malign capabilities. The West must indirectly remove Putin’s strategic options by shaping the perceptions of critical network players, making it clear that their interests and the patronal network itself are at risk. Accomplishing this end requires that NATO fundamentally challenge its assumption that Russia acts as a unitary state and create an attribution network resembling U.S. Army Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s team-of-teams approach to defeating al-Qaida in Iraq, but on a supranational level.

An effective attribution network would see the entirety of Russia’s malign influence in real time, understand the network’s switching mechanisms, and grasp the casual relationships between deterrent actions and nodal responses, thereby informing a harmonized policy approach to defense, deterrence and dialogue. NATO, its members and its societies already maintain a loose network of ad hoc partnerships and organizations of Russia watchers, but neither the Alliance nor its members comprehensibly detect nor fully appreciate noncontiguous threats due to information stovepiping. Solving attribution ownership requires the creation of a standing international, intergovernmental and intersocietal organization, fashioned in the image of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center or the European External Action Service’s Intelligence Center. An organization incorporating Celina Realuyo’s critical elements of collaborative models for security and development: “political will, institutions, mechanisms to assess threats and deliver countermeasures, resources, and measures of effectiveness” could ostensibly meld the existent web of Russia watchers with the hierarchical structures of NATO and the governments it defends. This approach has significant sovereignty, agency and fiscal limitations, but there may be a more expedient path to holistic attribution.

NATO already leverages a loose constellation of input networks spanning military, law enforcement, civil defense and academia. Broadening the participation in these groups, and clearly articulating their mandate, could garner significant attribution capability and capacity. Additionally, NATO should consider broadening the mission, manning and capabilities of the Multi-National Corps and Divisional Headquarters to include greater joint, interagency and intergovernmental partners to maximize individual alliance member expertise to inform more rapid and synchronized responses, whether they be multi-, bi- or unilateral. Networked structures such as these would embody the essence of former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis’ approach to long-term strategic competition outlined in the summary of the 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy, and are necessary to ensure “the seamless integration of multiple elements of national power — diplomacy, information, economics, finance, intelligence, law enforcement and military,” as well as providing a permanent point of interface with academia, nongovernmental organizations and corporations with interests jeopardized by Russian aggression.

Sobelman asserts that, “in theory, deterrence succeeds when a potential challenger, having received a credibly perceived threat, calls off an intended action.” While the West has taken some deterrent actions, Russia’s continued subconventional activities offer stark evidence that Putin and his network are undeterred. While NATO rightfully improves military capability, interoperability and strategic mobility, it must also account for Sobelman’s assessment that “military capabilities will not necessarily deter a challenger that believes that is has devised an effective way to offset their impact or escape them.” Credible military capability is an indispensable component of deterrence, but deterring Russia requires a collaborative attribution network built upon McChrystal’s twin pillars of “shared consciousness” and “empowered execution.” Formulation of effective deterrence and compellence measures requires an understanding of a hybrid state’s network, its internal decision dynamics and the interests of its actors. In the case of a revanchist Russia, greater network understanding will not only inform Western deterrence efforts, but also offer insight into the branches and sequels of the post-Putin era.

Chief of the Russian General Staff Gen. Valery Gerasimov noted in 2013 that “no matter what forces the enemy has, no matter how well-developed his forces and means of armed conflict may be, forms and methods for overcoming them can be found. He will have vulnerabilities and that means that adequate means of opposing him exist.” While debate continues as to the intent of Gerasimov’s comment, Galeotti notes that there is nothing “conceptually novel about current Russian practices,” as they include “using all kinds of nonkinetic instruments to achieve its ends.” The West already possesses adequate means to oppose the illicit actors and tactics constituting Russia’s array of subconventional aggression, for they are already in use, albeit desynchronized in their execution and informed by the unchallenged assumption that Russia acts as a unitary state.

While improved conventional deterrence and holistic resilience efforts are indispensable components of a revised deterrent construct, a successful Alliance strategy must necessarily embody structural and organizational changes that facilitate cross-government, civil-military cooperation. Development of a functional collaboration network will illuminate the linkages and vulnerabilities of Russia’s opaque network of malign influence facilitators. Deterring a hybrid Russian state requires a construct that harmonizes unitary-state deterrence and NSA compellence, incorporating denial of objectives and punishment of actions, facilitated by specific and credible dialogue.

Embracing a Revised Mindset

Traditional deterrence constructs fail to substantively address the asymmetric actors increasingly employed by revisionist states. Challenges posed by relatively weak but highly networked NSAs continue to confound Western governments, undoubtedly informing adversarial strategies. Western adversaries’ takeaways from this are threefold: 1) the West effectively initiates but ineffectively responds to subconventional competition; 2) direct Western conventional competitive advantage can be indirectly countered through the introduction of subconventional actors that are ambiguous and deniable in nature; and 3) hybridized governance structures confuse Western policy responses, creating opportunities to block, disrupt and spoil Western initiatives.

As a result, agenda-setting and effective competition in a highly networked environment will require states to embrace a deterrent mindset shift, thus informing innovative approaches to achieve desired policy outcomes. As Gen. Mark Milley, chief of staff of the U.S. Army stated, “The nature of war — the use or threat of violence, as an extension of politics, to compel the enemy … is immutable. However, the character of war … changes due to unique geopolitical, social, demographic, economic and technological developments interacting, often unevenly, over time.” While the nature of warfare is immutable, the character of the actors engaged in geopolitical competition is changing, requiring the West to operationalize U.S. Adm. James Stavridis’ “whole of international society approach” to counter hybrid state adversaries. The distinct implications of the hybrid state actor necessitate that deterrence thinking evolve or risk failure.

Comments are closed.