Russia’s Weaponization of International and Domestic Law

By Mark Voyger Senior lecturer, Russian and Eastern European studies, Baltic Defence College

Russia’s attempts to assert its hegemonic ambitions against Ukraine and other countries in its “near abroad” — what Moscow perceives as a region of its privileged interests — have posed serious challenges not only to the security of the region, but to the international order. During its ongoing comprehensive hybrid warfare campaign against Ukraine, the Kremlin has employed a full range of nonmilitary tools (political, diplomatic, economic, information, cyber) and military ones — conventional and covert. Given the prominent role of Russia’s information and cyber warfare, those two hybrid warfare domains have received most of the public attention and analytical effort so far.

However, there is a third pivotal element of Russia’s hybrid toolbox — “lawfare” (legal warfare), which is critically important and equally dangerous, but has remained understudied by the analytical community and is effectively still unknown to the public. Given lawfare’s central role in Russia’s comprehensive strategy, Russia’s neighbors, NATO and the West must develop a deeper understanding of this hybrid warfare domain and design a unified strategy to counter this major challenge to the European security architecture and the entire world order.

Definitions of lawfare

The term lawfare was first coined by retired U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. Charles Dunlap, a former deputy judge advocate general and now a professor of international law at Duke University. His 2009 paper “Lawfare: A Decisive Element of 21st-Century Conflicts?” defined lawfare as “a method of warfare where law is used as a means of realizing a military objective.” He broadened the definition in a 2017 article for Military Review to include “using law as a form of asymmetrical warfare.” Those original definitions focus on the exploitation of the law primarily for military purposes, which is understandable, given that the term hybrid warfare did not enter Western political parlance until the summer of 2014 with its official adoption by NATO. Given the prevalence of nonmilitary over military means (not only in an asymmetric military sense) in Russian Gen. Valery Gerasimov’s new generation warfare model, presented in February 2013, it is necessary to revisit and broaden the original definition of lawfare in a holistic fashion to place it in its proper context as one of the pivotal domains of Russian hybrid warfare. In Gerasimov’s 2016 update in the Military-Industrial Courier to his original model (based on Russia’s military experiences in Syria), he stated, “Hybrid Warfare requires high-tech weapons and a scientific substantiation.” In that regard, Russian lawfare’s primary function is to underpin those efforts by providing their legal foundation and justification. To be precise, the term lawfare itself does not exist in Russian, but the 2014 Russian military doctrine recognizes the use of legal means among other nonmilitary tools for defending Russia’s interests.

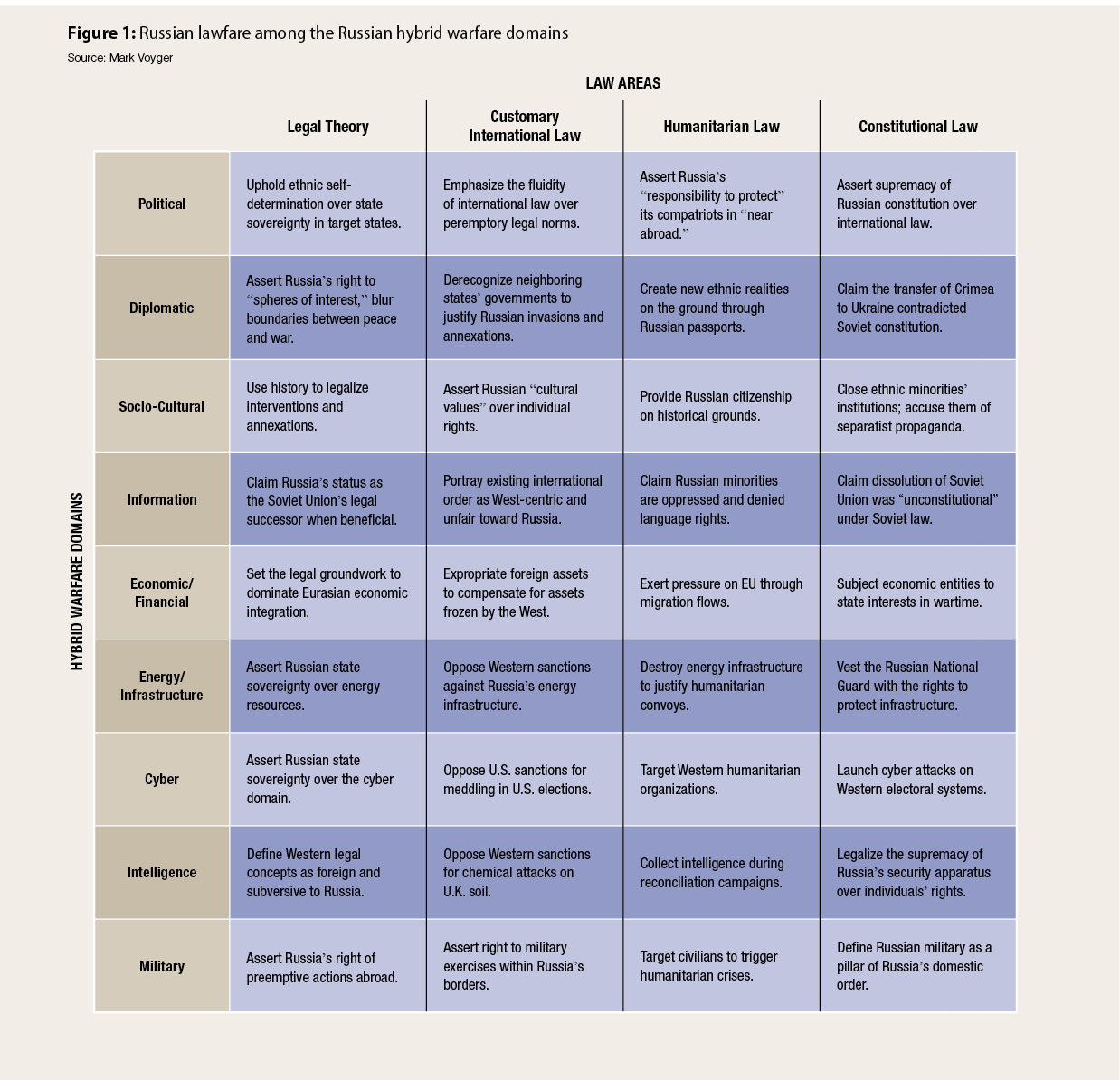

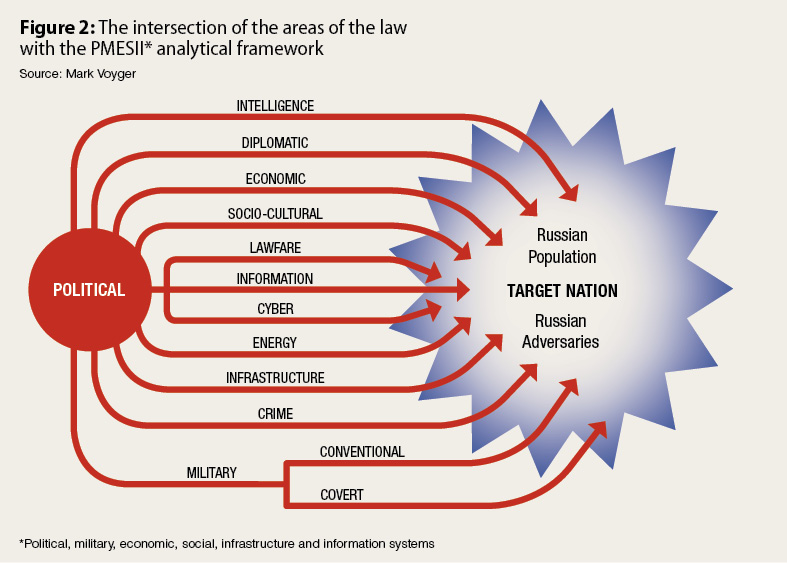

Russian lawfare is the domain that intertwines with and supports Russian information warfare, thus providing (quasi) legal justifications for Russia’s propaganda claims and aggressive actions. To provide further granularity, the legal domain of Russian hybrid warfare can be understood in its entirety only through the comprehensive analysis of the intersection of the areas of the law with the various other military and nonmilitary domains of hybrid warfare.

Russian lawfare’s imperial origins

Russian lawfare’s imperial origins

Russia has been using international law as a weapon since at least the 18th century. The roots of this type of conduct can be found in the history of Russian and Soviet interactions with the international system of nation states known as the “Westphalian order.” At various times in its history Russia has either been invited to join the concert of major European powers or invaded by some of those powers. In its formative centuries, the nascent Russian Empire did not deal with neighboring states as equals, but took part in their partition (the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) and the division of Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. It also regularly acted to suppress ethnic nationalism within its own territories, while at the same time encouraging Balkan nationalism and exploiting the ethno-religious rifts within the Ottoman Empire throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. International law was pivotal for Russia’s expansionist agenda because it claimed that the 1774 Treaty of Kucuk-Kaynarca with the Ottomans had granted it the right to intervene diplomatically and militarily in the Balkans as the sole protector of Orthodox Christians. Based on that fact, 1774 should be regarded as the birth year of Russian lawfare. This method for justifying imperial expansionism thrived during the Soviet era as the Soviet Union partitioned states, annexed territories, and launched overt aggressions and clandestine infiltrations across national borders in the name of protecting and liberating international workers, but really to impose its limited sovereignty doctrine on its satellite states.

This twisting and permissive reinterpretation of history to justify ex post ante Russia’s acts of aggression against its neighbors was codified on July 24, 2018, when the Russian Duma adopted a law recognizing officially April 19, 1783, as the day of Crimea’s “accession” to the Russian Empire. Catherine the Great’s manifesto proclaiming the annexation of Crimea is a diplomatic document that had an impact far beyond the borders of Russia and throughout the centuries that followed, and it has regained relevance in present-day Russian strategy. It is unique also in that Empress Catherine II employed arguments from all domains of what we nowadays refer to as hybrid warfare — political, diplomatic, legal, information, socio-cultural, economic, infrastructure, intelligence and military (both conventional and clandestine) — to convince the other Great Powers of Europe, using the 18th century version of strategic communications, that Russia had been compelled to step in to protect the local populations in Crimea. In that regard, April 19, 1783, can be regarded as the official birthdate of Russian hybrid warfare, in its comprehensive, albeit initial form, enriched later by the Soviet traditions of clandestine operations, political warfare and quasi-legal justifications for territorial expansionism.

It is noteworthy that the Russian word “принятия”

[prinyatiya] used in the text of the 2018 law literally means “to accept,” and not “to annex” or “incorporate.” The authors expressed their confidence that setting this new commemoration date affirms the continuity of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol as part of the Russian state. This legal reasoning contravenes the fact that, in territorial terms, the Russian Federation of today is the successor of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) as a constituent part of the Soviet Union, and not of the Russian Empire, and that the RSFSR only incorporated Crimea from 1922 until 1954.

After the Soviet collapse, the use of lawfare allowed Russia to justify its involvement in Moldova (that enabled the creation of a separatist Transnistria) in 1992, the 2008 and 2014 invasions of Georgia and Ukraine respectively, and the 2014 annexation of Crimea, not to mention Russia’s involvement in Syria in 2016, because these were all presented as essentially humanitarian peacemaking efforts. In all those cases, Russia claimed that friendly local populations or governments had turned to it for help, and that Russia felt compelled to answer that call and take those populations under its “protection,” thus also assuming control over their ethnic territories and domestic politics. The successful operationalization of this lawfare tool poses serious future dangers for all of Russia’s neighbors because it codifies a quasi-legal justification for Russia’s “peacemaking operations” that no longer requires only the presence of ethnic Russians or Russian speakers for the Russian state to intervene — it can also be employed to “protect” any population that has been declared Russia-friendly, regardless of its ethnic origin.

All these examples clearly demonstrate how Russia has been trying to amalgamate international and domestic law with categories often as vague and contested as history and culture for the purposes of implementing the Russian hybrid expansionist agenda. While these are nothing more than elaborately fabricated pretexts for Russian aggression, the fact that they have been allowed to stand de facto enables Russia to continue employing them against its various nation-state targets.

21st-century lawfare

International law dealing with conflict between states has evolved to prevent war through negotiations and agreements, regulate the right to go to war and set the rules of engagement, and normalize postwar relations through cease-fires, armistices and peace treaties. International law, in its modern interpretation, was not intended to sanction and justify the invasion and annexation of territories the way it is being used by Russia against Ukraine. The main systemic challenge that Russian lawfare poses is that customary international law is not carved in stone because it also derives from the practices of states, and thus in many ways is ultimately what states make of it. This fluid, interpretative aspect of international law is being used by Russia extensively and in the most creative ways to assert its numerous territorial, political, economic and humanitarian claims against Ukraine, as well as to harass regional neighbors in its perceived post-Soviet sphere of influence. So far, the existing international system based on treaties and international institutions has failed to shield Ukraine from the aggressive resurgence of Russian hegemony. Ukraine has submitted claims against Russia at the International Court of Justice on the grounds that Russia’s activities in Donbas and Crimea support terrorism and constitute racial discrimination, but it has not been able to challenge Russia on the fundamental issues of Crimea’s occupation and illegal annexation, and the invasion of Donbas.

While Russia does not have full control over the international legal system, and thus is not capable of changing its rules de jure, it is definitely trying to erode many of its fundamental principles de facto. The primary one is the inviolability of European national borders that were set after World War II, codified at Helsinki in 1975 and recognized after the end of the Cold War, including by the Russian Federation. Another legal principle that Russian lawfare severely challenges is the obligation to adhere to international treaties, pacta sunt servanda, although the Russian leadership constantly pays lip service to it and regularly accuses other signatories of international treaties and agreements (the United States, Ukraine) of violations or noncompliance. The full domestic and international sovereignty of nation states that is the cornerstone of the existing Westphalian international system is yet another fundamental principle eroded by Russia’s actions. To compound things, the universally recognized right of self-determination is used by Russia to subvert Ukraine’s unity as a nation state by elevating the status of the ethnic Russian and Russian-speaking Ukrainian citizens in Crimea, Donbas and elsewhere to that of separate “peoples.”

Russian lawfare actions range from strategic to tactical, depending on specific objectives at any point in time. Some specific examples since the beginning of the Russian aggression against Ukraine include a draft amendment to the law on the admission of territories into the Russian Federation that would have allowed Russia to legally incorporate regions of neighboring states following controlled and manipulated local referenda. This particular draft law was removed from the Duma agenda on March 20, 2014, by request of its authors following the Crimea referendum of March 16, 2014. Nevertheless, the fact that it was submitted to the Duma on Friday, February 28, 2014, barely a day before “little green men” — masked soldiers in unmarked green army uniforms and carrying modern Russian military weapons — appeared in Crimea and its subsequent occupation indicates the high level of coordination between the military and nonmilitary elements of Russian hybrid efforts, especially in the lawfare and information domains.

The legislative onslaught continued in April 2014 with a draft amendment proposing to grant Russian citizenship based on residency claims dating back to the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire, because it was targeting primarily Ukrainians. The annexation of Crimea and the invasion of eastern Ukraine in the spring of 2014 enabled Russia to expand another subversive practice — giving away Russian passports to boost the number of Russian citizens in neighboring states (aka “passportization”). This lawfare technique was used against Georgia to portray the Russian occupation and forced secession of Georgia’s Abkhazia and South Ossetia territories as legitimate actions in response to the will of local “Russian citizens,” coupled with the newly redefined Russian right of “responsibility to protect.” The scope and definitions of that particular right have proven to be extremely flexible since it was proclaimed in the Medvedev Doctrine of 2008. The initial intent to protect Russian citizens abroad later expanded to include the protection of ethnic Russians in Crimea, and then of Russian speakers in eastern Ukraine in 2014. Then in June 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin postulated the concept of the “Russian World” (“Russkiy Mir”) — a supranational continuum composed of people outside the borders of Russia who are to be bound to it not only by legal and ethnic links, but by cultural ones, too. Thus, Russia proclaimed its right to tie an affinity for the Russian culture writ large (Russian poetry, for example) of any category of people to their right to legal protection by the Russian state, which would be understood as a Russian military presence.

In the military sphere, the exploitation of loopholes within the existing verification regime set by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Vienna Document of 2011 has proven to be particularly advantageous for Russia and difficult for NATO to counter effectively. The most notorious lawfare technique that Russia has been applying since 2014 is the launching of no-notice readiness checks (snap exercises) involving tens of thousands of Russian troops. Such military activities obviate the Vienna Document and run contrary to its spirit and the intent to increase transparency and reduce tensions in Europe. Paradoxically, this is made possible by the loophole contained in Provision 41, which stipulates: “Notifiable military activities carried out without advance notice to the troops involved are exceptions to the requirement for prior notification to be made 42 days in advance.” In this case, the Russian modus operandi involves a major Russian news agency issuing a communique on the morning of the exercise stating that President Putin had called Minister of Defense Sergei Shoygu in the early hours of that morning to order him to put the Russian troops on full combat alert — a simple but very powerful technique combining lawfare with information warfare. Russia has also been circumventing the requirement to invite observers to large exercises by reporting lower numbers than the observation threshold of 13,000 troops (the number it provides to the OSCE always curiously revolves around 12,700) or by referring to Provision 58, which allows participating states to not invite observers to notifiable military activities that are carried out without advance notice to the troops involved unless these notifiable activities have a duration of more than 72 hours. In those cases, Russia simply breaks down the larger exercise into separate smaller ones of shorter duration.

Russia has also long been exploiting international law through organizations, such as the United Nations and the OSCE, for a range of purposes, such as blocking adverse U.N. resolutions through its veto power, garnering international support for its actions, or portraying itself as a force of stability and a peacemaker in Ukraine and the Middle East. Russia also reportedly uses those structures for influence operations or for intelligence gathering, for example, by having the Russian observers in the OSCE provide reconnaissance of the Ukrainian military’s disposition in the Donbas. Other examples include Russian attempts in 2014 to use the U.N. Security Council to sanction the opening of “humanitarian corridors” in the Donbas; presenting Kosovo and Libya as legal precedents for Russian actions; the sentencing of high-ranking Ukrainian officials in absentia by Russian courts; and multiple Russian allegations that Ukrainian authorities have triggered a humanitarian catastrophe in the Donbas, in an attempt to justify the overt deployment of Russian troops under the guise of “peacekeepers.”

Vulnerable areas and relevant responses

Areas that continue to be vulnerable to the effects of Russian lawfare are primarily the territories in Ukraine under Russian occupation, such as Crimea and the Donbas, but also the so-called frozen conflicts in Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh. They all contain multiple, intertwined and often mutually exclusive historical narratives based on complex socio-cultural realities that provide fertile ground for Russia’s presence and involvement under the quasi-legal pretext of stabilization efforts.

Ukraine has also recognized the power of historical narratives as a counter-lawfare tool. According to an August 2018 poll of Ukrainian public opinion by the Rating Group of Ukraine, more than 70% of Ukrainians believe that Ukraine, and not Russia, is the rightful successor of the Kievan Rus. The Ukrainian state must capitalize on those social trends to develop a coherent strategy targeting domestic and international audiences and institutions to counter Russia’s malicious exploitation of Ukrainian history for the purposes of disinformation and lawfare-based expansionism.

Similar cultural claims have been used as pretexts by Russia to put pressure even on its traditional allies, such as Belarus. The 2014 Russian military doctrine refers to it as “Belorussia,” its Russian imperial and Soviet name, and the Russian military has been pushing to expand its presence in Belarus by requesting additional bases on its territory. Most Belarusians use the Russian language for daily interactions and communication. In the age of Russian hybrid warfare, when culture is used to fabricate legal pretexts, the Belarusian leadership has recognized that very real threat and is taking steps to improve the population’s cultural awareness and language skills.

Unresolved border disputes with Russia also pose potential threats because Russia can exploit those to infiltrate NATO territory or to claim that NATO troops are provocatively close to its territories. Russia has been using border negotiations as tools of influence against its neighbors, particularly Estonia. After more than two decades of negotiations, the Russian Duma announced that it would ratify the bilateral treaty on February 18, 2014, less than two weeks before Russian forces infiltrated and occupied Crimea, and likely an attempt by Russia to secure its Western borders with NATO prior to launching its operation in Ukraine. The issue of the Russian-Estonia border was raised again in the summer of 2018, when Russia reneged on its commitment to ratify the treaty, explaining it as a result of Estonia’s “anti-Russian” attitudes.

Russia, of course, does not enjoy free reign in the sphere of international law, and it can prove to be a double-edged sword when the targets of Russian lawfare, in particular the Baltic states and Ukraine, decide to use the law proactively to defend themselves. The recent announcement by the ministers of justice of both Estonia and Latvia that they are exploring legal options to demand compensation from Russia — as the legal successor of the Soviet Union — for damages from the Soviet occupation is a timely example of how this internationally recognized Russian legal status can also be leveraged for counterclaims.

Apart from history and culture, Russian lawfare has also integrated and used skillfully the domain of science in the Arctic and the High North, particularly geology, chemistry and oceanography. The 2014 Russian military doctrine clearly identifies “securing Russian national interests in the Arctic” as one of the main tasks of the Russian Armed Forces in peacetime. After ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1997, Russia began to exploit the loophole provided by Article 76 to push for the expansion of its exclusive economic zone from 200 to 350 nautical miles, based on the claim that the Lomonosov Ridge that stretches for 1,800 kilometers under the Arctic Ocean is a natural extension of Russia’s continental shelf. The legal and scientific debates over the geological definition and chemical composition of that shelf could have huge ramifications. If Russia’s claim ultimately succeeds, according to Eric Hannes in a March 2017 U.S. News and World Report article, it would add more than 1.2 million square kilometers, with vast hydrocarbon deposits, to Russian Arctic sovereignty. While waiting for the legal case to be adjudicated by the U.N., Russia has gradually expanded its military presence in the Arctic in a clear attempt to combine legal and lethal arguments in its ongoing quest to dominate this strategic region, as the effects of global warming open its sea routes to navigation.

Lawfare provides numerous advantages to Russia. So far, it has proven to be less recognizable than its counterparts in the information and cyber domains. It successfully exploits the loopholes of international legal regimes, uses diplomatic negotiations as a delay tactic, and can create dissent and confusion among allies by exploiting legal ambiguities. On the other hand, by observing the patterns of Russia’s weaponization of the law as an element of its hybrid strategy against target nations, such as Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova, NATO can identify early signs of similar actions targeting other countries in its neighborhood, in particular its Baltic member states. The primary utility of tracking and analyzing Russian legal maneuvers is that acts of lawfare, by default, cannot remain completely secret. They are meant first and foremost to justify Russia’s actions in the international arena, and therefore, they must be employed overtly — either as a Russian legal claim, as a new law promulgated by the Russian parliament, as a decree issued by the Russian presidency, or as a troop deployment request approved by the Russian senate.

While such overtness may appear paradoxical for a society such as Russia’s, where secrecy and conspiracies have traditionally substituted for public policymaking, when it comes to the legal preparation of the battlespace, secret laws cannot serve the Russian leadership to defend their aggressive moves internationally or in mobilizing domestic support. In addition, since the preparation of those highly creative legal interpretations and pushing draft bills through the Russian legislature requires certain procedural efforts, if identified sufficiently early, the process can serve as an advance warning indicating the direction of future Russian political or military steps, both domestically and internationally. To achieve this, the Western analytical community would have to clearly recognize lawfare as a domain of Russian hybrid warfare, and track and analyze Russian legal developments on a continuous basis. The expansion of the DIME model (diplomatic, information, military and economic) of national power to DIMEFIL by adding financial, intelligence and legal, is definitely a step in the right direction, but “L” also should be added to the PMESII (political, military, economic, social, information and infrastructure) analytical framework that describes the effects of the comprehensive preparation of the environment/battlefield through DIMEFIL actions.

Defending against Russian lawfare, of course, is not solely the task of analysts. A comprehensive strategy to counter its tools and impact can only be elaborated on and applied successfully by the coordinated efforts of political and military leaders, legal and academic experts, and the institutions they represent across borders and multiple domains. This would require constant and firm emphasis to be placed on upholding and strengthening the peremptory norms of international law at all levels — from the U.N. level through the international courts system to various university law departments. The political leadership and the media organizations of NATO and partner nations must constantly seek to expose proactively (hand-in-hand with the experts in countering Russian information warfare) the ulterior motives and aggressive purposes behind Russia’s “peacemaking” campaigns; vehemently oppose Russia’s claim to its “responsibility to protect” in its self-perceived sphere of interest; incessantly seek opportunities to close existing loopholes in international agreements that Russia exploits; and as a rule of thumb, always approach negotiations with Russia as a multidimensional chess game that requires constant awareness that Russia’s moves look many steps ahead and across all domains.

Lawfare Defense Network

Given that lawfare is a pivotal element of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategies against Ukraine and the West, the response must be holistic and comprehensive in nature. It would require the building of a network of lawfare study programs (a Lawfare Defense Network) at various universities and think tanks — first and foremost in Ukraine, but also throughout Eastern, Central and Southern Europe, in countries such as Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Serbia and Georgia, as well as in the U.S. and the United Kingdom. This network’s ultimate goal would be to generate interest and support among NATO and EU member states’ legislators, political leadership and publics to establish a Lawfare Center of Excellence, just like the ones dealing with strategic communications (Riga, Latvia), cyber defense (Tallinn, Estonia) and energy security (Vilnius, Lithuania). It could be based in a NATO or a European Union member state or in an aspirant country such as Ukraine. Regardless of the future location, Ukraine and the Baltic states must be at the forefront of this initiative, morally, given that they have been the primary target of Russian lawfare for centuries, and practically, by performing the main body of research and analysis of ongoing Russian lawfare activities. Once these programs are established and fully operational at various think tanks and universities, they can focus on their specific country’s lawfare challenges to better leverage their national capabilities. The future Lawfare Center of Excellence will then compile and analyze all the national input and provide practical, feasible recommendations to national governments and NATO.

Conclusion

The continuous evolution of Russian lawfare is proof of Russia’s legal creativity in bending and reinterpreting international law to achieve its strategic objectives. While Russia publicly demonstrates ostentatious respect for international law, it has undoubtedly espoused a revisionist view of international law based on the concept of Great Powers’ spheres of influence and a self-proclaimed right of intervention that challenge the main tenets of security arrangements in Europe and beyond. If its lawfare activities continue unchecked, Russia will be emboldened to continue applying those methods to justify its expansionist and interventionist policies in all areas that it regards as legitimate spheres of interest. Quite inevitably, other great and regional powers have already followed suit and are resorting to lawfare tools to lay claims on contested areas (China) or justify their presence in volatile regions (Iran). The Middle East, Africa and Asia are particularly vulnerable to the application of lawfare, given the disputed, even arbitrary, nature of many state borders there. But some NATO members are also not immune, especially those with sizable Russian-speaking populations or unresolved border disputes with Russia. Russia’s use of lawfare as a primary domain of its comprehensive hybrid warfare strategy poses structural challenges to the stability of the international security system and the foundations of the international legal order and, therefore, a cohesive Western response is needed to successfully counter it.

This article is excerpted from the Baltic Defence College publication, NATO at 70 and the Baltic States: Strengthening the Euro-Atlantic Alliance in an Age of Non-Linear Threats.

Comments are closed.