The Implications of Opening Access to China

By Anne Clary, Ph.D. candidate at the Graduate School of Politics at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität in Münster, Germany

In May 2021, Hungary announced plans to open a branch of the Chinese Fudan University in Budapest. The new campus marks the first time China has exported a university satellite campus to a European Union member. The announcement follows the removal of Hungary’s postgraduate Central European University (CEU) in 2019, which was famously forced out of the country through changes to education law and has since relocated to Vienna, Austria. Both developments have sparked public protests in Hungary by those who say the country’s own higher education system is being undercut to advance Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s illiberal agenda. For China, the move is part of its overall geopolitical One Belt, One Road policy (OBOR) to take the lead in globalization, develop its higher education and research systems, and actively seek Western academic partners to attract talent. While these goals are often achieved in legitimate ways, the authoritarian nature of the Chinese regime raises concerns about its motives and its tactics. For the EU to strengthen its competitiveness in a shifting and globalized world, it remains imperative for its academic community, including policymakers, scholars and students, to do a better job of studying and understanding China.

Heightened political tensions between the EU and China are adding new layers of complexity to academic collaborations, and EU stakeholders are beginning to recalibrate these partnerships. Possible protective measures include scrutiny of university agreements, skepticism toward the goals of China’s authoritarian regime, and calls for transparency in the funding and internal governance of universities. These measures could help strengthen the defenses of the EU’s higher education systems and institutions against misuse by China. Hungary illustrates why EU member states must uphold EU laws to protect the bloc’s security interests, academic and otherwise, from malign foreign influence.

Budapest: A Tale of Two Universities

In March 2017, CEU found itself the object of a law passed by Hungary’s parliament that, according to CEU’s president and rector at the time, came as a surprise. The law’s purpose was to outlaw the structure of the Hungary-United States partnership that established the highly respected university 26 years earlier. Among its key consequences were: 1) the end of the university’s dual Hungarian and American legal identity; 2) the requirement that the university chooses either a Hungarian or an American accreditation; 3) the establishment of a CEU campus in the U.S.; and 4) a new agreement between Hungary and the U.S. Additionally, the bill restricts non-European universities from entering into cooperation with Hungarian universities.

The new education law quickly became known as “Lex CEU” (or the CEU law) because, critics contend, it specifically targeted CEU. At the time, CEU consisted of two legal entities: CEU, accredited in the U.S., and Közép-európai Egyetem (CEU’s Hungarian name), a private university accredited in Hungary. Both entities operated in Budapest, but a majority of CEU’s programs received U.S. accreditation. University supporters argued that because of the majority international makeup of CEU’s student body, depriving the university of the possibility of offering U.S. degrees would have detrimental consequences for CEU’s status. However, then-Hungarian State Secretary Pál Völner said the legislation was needed to level the playing field between Hungarian universities and the 28 foreign universities that operate in the country. Völner further explained that the law ensures the transparent flow of money in the civil sector and holds nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) legally accountable for political actions.

The latter highlights what many opponents saw as the main purpose of the law: to target George Soros, the CEU’s founder and Hungarian billionaire whose philanthropic efforts promote democratic values and open societies in former communist countries. Since its founding in 1991, CEU’s mission and international reputation have become increasingly at odds with Orbán and his ruling Fidesz party’s illiberal vision for the country. As Orbán has strengthened ties with authoritarian leaders within and outside of Europe, he has expanded the legal authority of the Hungarian government while maintaining that any changes to Hungarian law are well within the legal framework of the European Commission (EC). Nonetheless, the EC initiated a legal assessment of Lex CEU that same month, while thousands of protesters convened in Budapest the following month to oppose the law.

After a series of delayed and failed negotiations with the Hungarian government, CEU announced in December 2018 that it would move its campus to Vienna, and it resumed operations there in September 2019. The EC moved forward in its lawsuit against Hungary on the basis that the law is incompatible with EU legislation. In October 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled in favor of the EC and found that the law violated EU agreements with the World Trade Organization regarding fair market access as well as the provisions of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights protecting academic freedom and the freedom to conduct business. However, by 2020, the legal status of CEU in Hungary was moot. The university had already incurred a loss of 200 million euros in relocation expenses and had no plans to return to Hungary. Though handed a strong judgment by the CJEU, Orbán was ultimately successful in using the Hungarian and EU legal processes to achieve illiberal political gains.

In December 2020, less than four years after the CEU conflict began, Orbán announced that the Hungarian government would host the first Chinese university campus in the EU, with the construction of a Fudan University satellite campus in Budapest. The project was one of several initiatives underscoring Orbán’s focus on building closer ties with Beijing, despite rising Western European and American anxiety about China’s deepening influence over parts of Central Europe. By 2021, China’s investments and activities in Hungary were significant: the planned building of a new 4 billion euro rail line between Budapest and Belgrade, funded through OBOR; the increasing operations of the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei in Budapest; and now the proposed construction of the Fudan campus, estimated to cost 1.5 billion euros. For comparison, the entire operating budget for Hungary’s higher education system in 2019 totaled 1.3 billion euros.

Initial plans call for the Fudan satellite campus to open in 2024 and host 6,000 students. It plans to offer degrees in economics and international relations as well as medical and technical sciences, and Hungarian officials say they hope the campus will enhance the country’s higher education offerings and boost Chinese investment. However, the Hungarian government agreed to provide the initial funding for the construction and maintenance of the campus. Hungary also plans to contract the construction project to a Chinese company and finance it with a loan from a Chinese bank. Estimated operating costs are budgeted at 275 million euros from 2023 to 2027, and 45 million euros per year once the campus is fully established. At that point, according to the proposal, funding will be provided through the university’s foundation with contributions from China.

Thousands of protesters convened in Budapest in June 2021 to oppose the planned campus, angered by the combination of Hungarian taxpayers having to pay for its construction and plans to build it on property originally designated for low-cost student housing. Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony, an Orbán opponent, has strongly opposed the project, highlighting its costs to taxpayers, its use of public property for private interests, and the lack of public input regarding the development of the proposal itself. Karácsony has also noted that the Fudan campus poses a risk to academic freedom in Hungary by positioning Hungarian universities in direct competition with a more well-funded Chinese counterpart. However, some academics have rejected this notion, pointing out that Western and Chinese academics have been collaborating for decades and arguing that limiting the expansion of Chinese universities in Europe would damage scientific relations. In response to the protests, the Hungarian government announced it would hold a referendum on the proposal. But the Hungarian Constitutional Court ruled in May 2022 that holding the vote would be unconstitutional, effectively killing the referendum.

Areas of Consideration

The planned Fudan University satellite campus in Budapest provides an opportunity to assess the risks and realities related to China’s pursuit of a strong higher education presence in the EU. Considering the context of Hungary’s Lex CEU law and the subsequent removal of CEU from Hungary, several questions emerge. For example, what legal authority do EU member states have over their higher education institutions, and how can the CJEU effectively respond when EU laws are violated in this arena? Additionally, how can the EU, its member states and higher education institutions address the financial transparency, academic integrity and security issues that are becoming increasingly urgent in university partnerships with China? Finally, as the EU determines how to manage heightened hybrid security risks posed by Chinese and other foreign actors, how can its higher education institutions, faculty and students be protected from political polarization within the EU?

Chinese investment and government control

As previously noted, China’s investment in higher education opportunities in Europe is just one part of its overall OBOR expansion strategy. It is, however, an important part, with significant policy and financial commitments. By 2035, China aims to be one of the most powerful countries in terms of learning, research output and talent cultivation. In addition to strengthening its education sector domestically, China is intent on enhancing its international influence on education worldwide. Since 2012, China has spent 4% of its gross domestic product on education and has made an initial investment of 242 billion euros in the area of research and development. In June 2020, China’s Ministry of Education outlined several goals designed to enhance its international education ambitions. These include the expansion of joint degree programs with global partners, cross-border and overseas joint education programs and programs established by Chinese universities abroad. The Chinese government intends to achieve these aims through the removal of institutional barriers, improved facilitation of Chinese student and staff mobility globally, and an expansion of mutual recognition of academic credits and diplomas with foreign universities. Furthermore, China plans to increase the export of its university models around the world, expand Chinese language learning to more countries and strengthen the implementation of the 2016 Education Action Plan for OBOR.

China’s financial investment and policy implementation in its education initiatives demonstrate the country’s aim to be a major player in international education. China is signaling that it can adapt its higher education governance structures on an individual basis to be more compatible with partnering international institutions. This approach may be well suited for the EU, where higher education policies are essentially decided and implemented by individual EU member states. That is, each country can determine the teaching content and the organization of its educational system. However, this independence must be exercised within the framework of EU laws and principles. For example, according to the principle of equal treatment, EU member states cannot charge higher tuition fees for non-national EU students. In the EU, higher education institutions have the ultimate responsibility for the quality of their curricula. Universities are supported by external agencies, which assess quality standards, evaluate institutions and accredit programs.

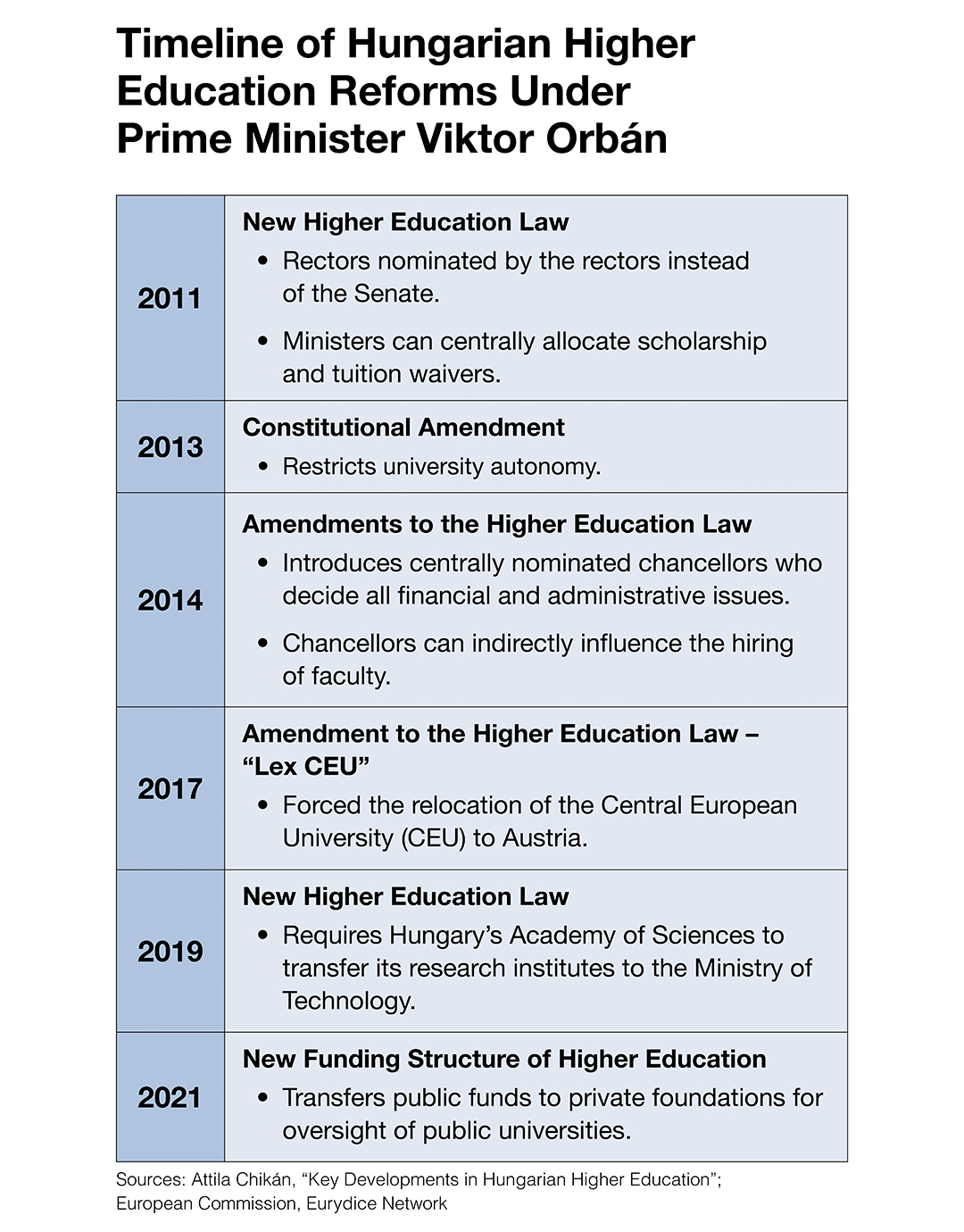

Before the passing of Hungary’s Lex CEU, the Orbán government had taken steps to assert greater influence over the country’s higher education system. Starting in 2010, when Orbán’s current period in office began, the Hungarian government introduced legislation aimed at overhauling and centralizing the country’s higher education governance structures. Among the changes were: 1) new mechanisms for supervision and institutional governance that reduced the institutional autonomy of universities; 2) new processes in the selection of rectors; 3) the introduction of state-appointed financial inspectors; and 4) newly state-appointed, nonacademic chancellors responsible for the finance, maintenance and administration of higher education institutions. Many academics took notice and raised concerns over these changes. However, the reforms were not entirely inconsistent with current trends in higher education within the EU, and other restrictive Hungarian legislation focused on the media, the courts and free speech garnered more international criticism.

Following the CJEU’s decision on Lex CEU, Orbán’s government passed additional higher education legislation in 2021 that restructured the administrative hierarchy governing Hungary’s 11 primary state universities by transferring oversight to organizations managed by private foundations. These foundations are expected to receive approximately 1.5 billion euros in government funding for their operations. Because Orbán’s Fidesz party holds a supermajority in the parliament, Orbán and party officials were able to revise the country’s Constitution to reflect this transfer of administrative powers. As China continues its ambitious pursuit of international higher education partnerships, Hungary has systematically signaled its willingness to reform its own higher education governance structures to be more compatible with China’s authoritarian regime.

Security risks at EU universities

Recognizing the increasing need for comprehensive frameworks when approaching university partnerships with China, EU stakeholders are establishing guidelines that protect their security interests. This is a notable shift in the EU’s approach to China, as more security risks emerge and EU public opinion of Chinese policies and activities becomes more negative. Warrants for concern include alleged espionage in Brussels and Chinese refusals to share research data in several partnerships. There is a growing concern about the undermining of international academic freedom through inappropriate forms of Chinese political influence. In 2019, Prague’s Charles University fired three faculty members and closed its Czech-Chinese Centre after investigations revealed they had received payments from the Chinese Embassy. The Free University of Berlin faced criticism from the German government after the university signed a contract binding it to Chinese law while accepting approximately 500,000 euros from China to establish a Chinese teacher training program. Critics said this would give the Chinese government leverage over teaching and scholarship on sensitive political and historical issues.

While the proposed Fudan University satellite campus would mark the first autonomous Chinese university in the EU, China’s presence within European universities has been commonplace since the opening of its first Confucius Institute in 2005 in Sweden. Confucius Institutes are funded by the Chinese government and located at hundreds of host universities worldwide. Initially seen as mechanisms of soft power for the promotion of Chinese language and culture, these institutes are undergoing increased scrutiny regarding concerns over Chinese political influence as a threat to academic freedom. At present, there are approximately 190 Confucius Institutes operating within EU universities, including five centers at Hungarian universities. As tensions between the West and China rise, some Confucius Institutes in Europe, the U.S. and Australia have been closed or had their contracts amended amid claims of espionage and political influencing. In Europe, several institutions decided not to extend contracts with the Confucius Institutes on their campuses, while Sweden became the first European country to officially end all partnerships in 2015. In response to the growing international criticism of Confucius Institutes, Beijing has transferred the governance of the centers from Hanban, the institutes’ headquarters, to an NGO. However, despite these concerns, most host universities, including in the EU, remain committed to hosting Confucius Institutes on their campuses.

Realigning partnerships

Other security issues related to Chinese influence in EU higher education include the presence at EU universities of researchers and students with links to the Chinese military, the adoption of dual-use technology that could potentially hack into university networks, and intellectual property theft. Growing Western criticism of China’s domestic and international policies, combined with China’s initial handling of the COVID-19 outbreak, has caused EU public opinion of China to decline significantly since 2020. These factors have placed additional pressure on EU universities to develop a consistent framework of governance and transparency in their Chinese partnerships. Efforts in this regard are underway on the part of several entities, including the EC, universities and NGOs. The EC released a draft version of “Tackling Foreign Interference in Higher Education Institutions and Research Organisations” in 2020 and updated its “Global Approach to Research and Innovation” in 2021. Both documents address the need for academic engagement with foreign entities, including China, to be open, reciprocal and focused. Even though these EC policies may not be implemented by all member states, the guidelines could prove helpful for individual universities in developing better safeguards of academic integrity.

On a national level, the German Rectors Conference (HRK), an association of 268 German universities, and The Hague Center for Security Studies (HCSS) think tank have produced guidelines for German universities and Dutch stakeholders, respectively. The HCSS’s “Checklist for Collaboration with Chinese Universities and Other Research Institutions” outlines 10 questions that help stakeholders weigh the advantages against the possible risks of collaboration with China. These questions are supported by examples of incidents and challenges that provide a rationale for risk assessment. HCSS states that the goal of the document is not to discourage cooperation, but rather to enhance its added value for the Netherlands. Though specific to stakeholders in the Netherlands, the document could be adapted and utilized as a concise and precise tool for enacting institutional measures elsewhere within the EU.

The HRK guidelines are specifically intended for German universities, but their questions are general enough to apply to stakeholders in other EU countries. These guidelines focus primarily on academic integrity and less on the strengthening of knowledge security. However, they do recommend that German universities work with the country’s Federal Academic Exchange Service when entering into agreements with China and offer suggestions for strengthening collaboration in diplomatic ways. Examples include showing mutual respect in collaboration with China and improving the integration of Chinese students into the university community. While Germany’s higher education system is managed at the level of the country’s 16 federal states, rather than its national government, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research announced its “China competence” initiatives in 2018 to promote a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of China throughout Germany’s education sectors.

If supplemented with the HRK guidelines, the China competence project at the university level could provide a road map for sincerely engaging with Chinese partners while protecting EU and academic security interests.

Even with the recent strain on EU-China relations, collaboration in higher education and research between the two has increased dramatically in recent decades. Such collaboration takes many forms, from student mobility to academic publishing and cooperation between businesses and research institutions. As such, universities also need to establish approaches to China that suit their specific interests and goals. A notable example of this effort is the Leiden Asia Centre’s report, “Towards a Sustainable Europe-China Collaboration in Higher Education in Research.” The report argues that to address increasing security challenges effectively, stakeholders in European higher education need to develop and implement approaches aimed at making collaboration with China more feasible. Doing so is not only in the interest of their security and the academic freedom of their faculty and students, but also beneficial for long-term competitiveness in research and reputation. The report makes a series of recommendations in advocating for effective collaboration between European universities and government organizations. In addition to taking protective measures, stakeholders should also develop an approach that allows them to identify opportunities for sustainable collaboration. Throughout the report, the authors emphasize that an important prerequisite for all cooperative endeavors is the expansion and deepening of Chinese expertise in Europe.

Political polarization of academia

As previously discussed, very real security breaches have occurred at universities on behalf of Chinese actors. However, higher education is not the only vulnerable sector, China is not the only foreign actor, and decreased collaboration with China could negatively affect EU universities in a globalized economy. Similarly, an increasingly politicized environment within the EU can negatively limit academic freedom and research at its universities. In the case of Hungary, while the status of CEU was still pending, a pro-government website asked students to submit the names of professors who espoused “unasked-for left-wing political opinions.” A Fidesz-friendly weekly published an “enemies list” that included the names of dozens of academics, “mercenaries” purportedly working on behalf of George Soros. Faculty at various Hungarian universities were fired for their work on human rights issues. Alternately, when the Fudan campus was announced, several of Orbán’s opponents quickly accused the facility and its operations of being a “spy harbor” for China. Although not a new tactic by any means, the political targeting of academia and other civil society actors puts the security of those targeted at risk.

Conclusion

Hungary’s relationship with China is unique in the EU. Orbán has indicated a willingness to dispose of democratic principles through legal reforms across varying sectors, including higher education. This opens the door to malign influence not only by China, but by other foreign actors as well. However, the EC, certain member states, NGOs and universities are developing protective frameworks to proceed prudently with China as a partner in higher education. These are important steps because the security risks are real and the threats are complex. Here, implementation is key, and cooperative mechanisms like Europe’s Bologna Process could serve as vehicles of facilitation for universities within its 47 member countries.

However, the guidelines are only effective if all member states are committed to upholding the liberal democratic values of the EU or are readily held accountable when they have violated EU norms and laws. Lex CEU is not the only Hungarian legislation that the CJEU has found to be in violation of EU law. The court has also recently ruled against Hungary on issues relating to asylum seekers and judicial interference. But the recent higher education reforms demonstrate Orbán’s ability to consolidate power. The EU’s 300 billion euro Global Gateway infrastructure strategy is meant to directly counter China’s OBOR policy and to protect its security interests while pursuing mutually beneficial engagement with China. For the EU’s strategy to succeed — for the sake of the long-term cohesion of the EU — it is increasingly imperative that its members’ governments commit to upholding EU laws and principles.

Comments are closed.